On a hot day in September, Charlene Jones celebrated her 61st birthday by herself.

The former nursing-home cook made herself a birthday dinner of turkey and dressing, macaroni and cheese, string beans and butter pound cake. She ate it alone, in a dim apartment in an affordable housing complex in Miami’s West Little River neighborhood.

“I wanted to be home,” Jones said. “I don’t really like being out.”

Jones’ health problems span the alphabet: asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). As average temperatures in South Florida continue to rise because of global warming, Jones is spending more time inside, trying to avoid heat that exacerbates her breathing problems and leaves her gasping for air. She schedules her appointments early in the morning or late in the afternoon to avoid the hottest hours of the day. The windows of her apartment are covered by thick curtains, but she doesn’t miss the sunlight.

“No,” she said. Sunlight means heat.

Florida has always been hot, but thanks to greenhouse gases trapping heat in the Earth’s atmosphere and driving up temperatures worldwide, the state has gotten hotter. In the past five decades, Miami and Tallahassee have been on pace to see 25 or more additional days per summer with temperatures above 90 degrees, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) compiled by the research center Climate Central, a nonprofit that receives funding from the U.S. government and private foundations. Other Florida cities, including West Palm Beach, Panama City, Pensacola, Tampa and Sarasota, are also seeing increases in the number of above-90 degree days per year. In fact, of the cities analyzed, only Gainesville showed the possibility of a downward trend, and a very slight one at that.

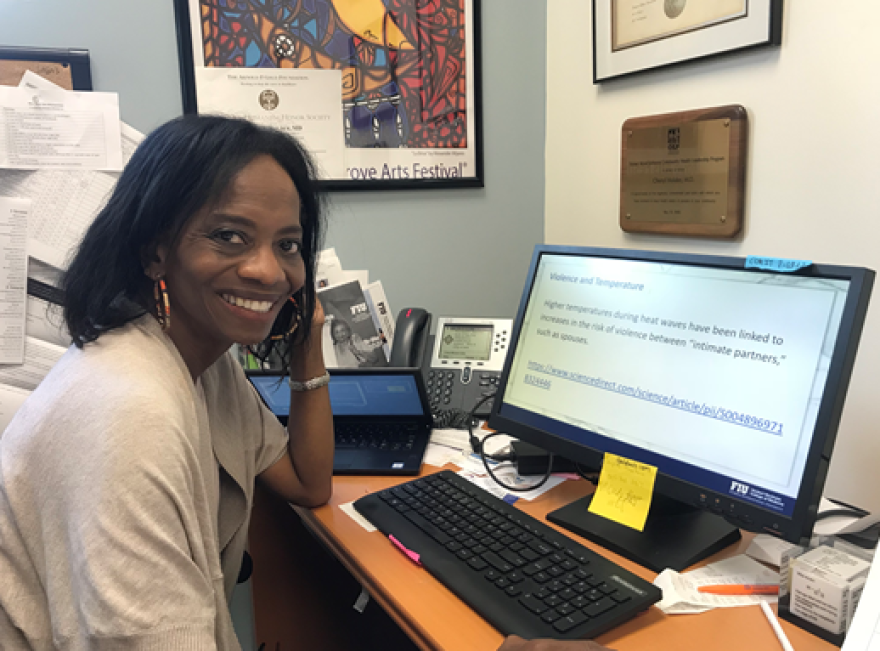

As heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise worldwide, temperatures will keep rising too. That worries Charlene Jones’ doctor, Cheryl Holder, an internal medicine specialist at Florida International University and president of the Florida State Medical Association.

“She’s doing her best,” Holder said of Jones. “I do tell her to try and avoid the exposure, but hearing that her windows are all blocked and dark, that’s not really what we want.”

But pulling the shades may be the only option for a patient like Jones. She’s already spending a lot of money on air conditioning, electricity for fans and medications to control her asthma, bronchitis and COPD. Right now, she’s also saving for a new car so she can drive to appointments instead of having to walk to the bus stop.

People who live on low incomes are among the most vulnerable to climate change. For patients who are susceptible to increasing heat, health care needs — air conditioning and fans, not just medications — may not be covered by health care programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

Holder says for those patients, doctors often recommend going to public places with free air conditioning, like a mall or a public library.

But to get there, patients still have to go outside. Like Jones, they may have to walk in the heat to a bus stop and wait for the bus in the sun, because many bus stops in Florida are uncovered.

“There’s no real escape,” Holder said.

And, she added, the health costs of increasing heat extend beyond the patients themselves. Local emergency medical services and the government health programs that support low-income patients are almost entirely funded by taxpayers.

Heat exacerbates different health conditions in different ways. It can worsen COPD by affecting pressure in the lungs and worsen asthma by making it harder for a person’s airways to expand.

“You feel like you can’t exhale and you can’t breathe in enough,” Holder said.

In addition to trying to limit patients’ heat exposure, doctors try to treat this tightness with medications and treatments like nebulizers and inhalers. But those can be expensive and time-consuming to administer: Jones has to hook herself up to a nebulizer — a machine that converts her medication into an aerosol mist she can breathe in — in her living room every six hours during the day.

Heat can increase risk for patients with heart disease or other cardiac conditions. When it’s hot, blood flow to the skin needs to increase to help direct heat out of the body. But that requires the heart to pump faster and harder. The extra stress can cause heat exhaustion, heat stroke or heart attacks.

Under particularly extreme conditions, heat also can damage other organs such as the liver and kidneys. That was the case for many of the 12 senior citizens who died in sweltering conditions at a nursing center in Broward County last year after Hurricane Irma knocked out the facility’s air conditioning.

The impacts of heat on health can also be indirect. More hot days mean a longer allergy season, since flowers and trees bloom earlier and can stay in bloom longer. And there’s evidence mosquito season is getting longer as well — because of both an increase in mosquito-friendly hot days and in humidity that comes with another effect of climate change: heavier rainfall.

In South Florida, there’s some evidence that warmer weather may be contributing to an increase in the percentage of deaths from chronic lung conditions. Data from the Florida Department of Health shows that in the 1970s, lower respiratory conditions like COPD caused between one and two percent of all deaths in Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach counties.

Today, health department data shows lower respiratory conditions cause roughly five percent of all deaths in Southeast Florida and the Keys.

It’s impossible to say with certainty that rising global temperatures have directly caused an increase in the percentage of deaths in Florida from lower respiratory conditions. However, numerous studies show that heat makes those conditions worse.

Some Florida cities and counties have begun to respond to the health risks of hotter temperatures, and the particular threat to people who are elderly or on fixed incomes. The federal government does not require air conditioning in public housing, so the City of Miami recently installed 51 units for some residents with health conditions. Miami-Dade County is planning to plant a million trees by 2020 to provide shade and offset heat absorption by buildings and concrete roads.

In a regional climate compact among Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach counties, planners and policymakers identify extreme heat as a public health threat and recommend measures like opening new cooling shelters in response.

Holder, who’s a leader of the recently created Florida chapter of the group Clinicians for Climate Action, says it’s not enough.

“We have to get to the root of the problem,” she said. “We still have to get to decreasing fossil fuel (use).”

Earlier this month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — a United Nations group that leads research on global warming — released a report: The Earth is on track to cross a temperature threshold that means even more killer droughts, heat waves and water shortages. The planet will likely surpass that threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming above pre-Industrial Revolution levels by 2052 — and possibly as soon as 12 years from now.

To keep temperatures below that critical level, the scientists say, the world will have to make an effort to cut carbon emissions that’s unprecedented in human history.

9(MDAyNDY5ODMwMDEyMjg3NjMzMTE1ZjE2MA001))

Copyright 2018 Health News Florida