Updated October 22, 2021 at 2:11 PM ET

La Niña will be joining us for the winter again, according to federal forecasters.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center released its official winter outlook on Thursday, and confirmed that La Niña conditions will be in place from December to February.

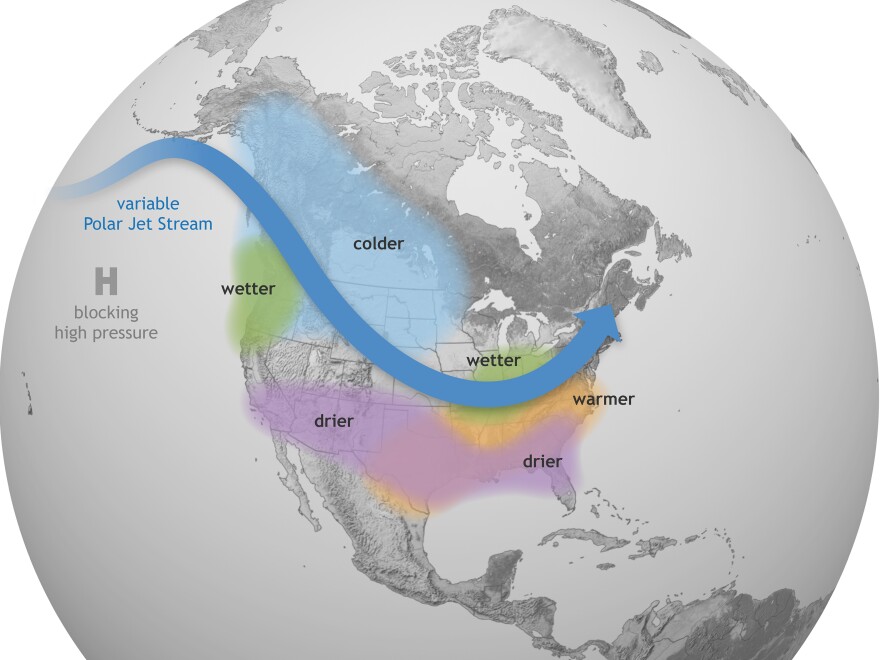

It's not a total surprise: NOAA announced earlier this month that La Niña conditions had already developed, with an 87% chance they would remain in place during that three-month period. Now it's forecasting wetter-than-average conditions across portions of the northern U.S., namely the Pacific Northwest, northern Rockies, Great Lakes, Ohio Valley and western Alaska.

La Niña (translated from Spanish as "little girl") is not a storm, but a climate pattern that occurs in the Pacific Ocean every few years and can impact weather around the world.

The U.S. is expected to feel its effects on temperature and precipitation, which could in turn have consequences for things such as hurricanes, tornadoes and droughts.

"Consistent with typical La Niña conditions during winter months, we anticipate below-normal temperatures along portions of the northern tier of the U.S. while much of the South experiences above-normal temperatures," said Jon Gottschalck, chief of the Operational Prediction Branch, NOAA's Climate Prediction Center. "The Southwest will certainly remain a region of concern as we anticipate below-normal precipitation where drought conditions continue in most areas."

Forecasters point out that this is actually the second La Niña winter in a row, a not-uncommon phenomenon that they call a "double-dip." The most recent period lasted from August 2020 to April 2021. (More below on what has happened since.)

Here's a primer on how La Niña works and what it could mean for different parts of the country.

What exactly is La Niña?

Scientists stress that La Niña is not a storm that hits a specific area at a given time. Instead, it's a change in global atmospheric circulation that affects weather around the world.

"Think of how a big construction project across town can change the flow of traffic near your house, with people being re-routed, side roads taking more traffic, and normal exits and on-ramps closed," states a NOAA webpage. "Different neighborhoods will be affected most at different times of the day. You would feel the effects of the construction project through its changes to normal patterns, but you wouldn't expect the construction project to 'hit' your house."

We'll start off with the technical explanation: It's one part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, a natural climate pattern defined by opposing warm and cool phases of oceanic and atmospheric conditions in the Pacific.

La Niña and its counterpart, El Niño, alternately cool and warm large areas of the tropical ocean about every two to seven years on average. (There's also a "neutral" state, which is where we've been since the last La Niña ended.)

As the agency explains (with a helpful flowchart), forecasters can officially declare a La Niña event when sea surface temperatures clock in below a certain level, are modeled to remain under that threshold and prompt a noticeable atmospheric response, like changes in winds.

Here's how that works.

"During normal conditions in the Pacific ocean, trade winds blow west along the equator, taking warm water from South America towards Asia. To replace that warm water, cold water rises from the depths — a process called upwelling," NOAA explains. "El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that break these normal conditions."

Trade winds are stronger than usual under La Niña conditions, so they push more warm water toward Asia. Meanwhile, off the west coast of the Americas, an increase in upwelling sends cold water toward the surface. (The nutrient-rich water also draws more cold-water species, like squid and salmon, to places such as the California coast.)

Cold waters cause the jet stream to move northward and then weaken over the eastern Pacific.

La Niña is here! And for the second straight year, it is expected to last through the northern hemisphere winter. Find out more at the ENSO Blog!https://t.co/ErmvatEtjp pic.twitter.com/ZfakWfeJGW

— NOAA Climate.gov (@NOAAClimate) October 14, 2021

So what does that actually feel like on the ground?

The biggest impact of La Niña on North American rain, snow and temperatures tends to be felt during the winter, according to NOAA.

Generally speaking, La Niña winters tend to be drier and warmer than normal across the southern U.S. and cooler and wetter in the northern U.S. and Canada.

NOAA says that this year, warmer-than-average conditions are most likely across the southern part of the U.S. and much of the eastern U.S., with the greatest likelihood of above-average temperatures in the Southeast. Below-average temperatures are favored for southeast Alaska and the Pacific Northwest eastward to the northern Plains.

The Pacific Northwest, parts of the Midwest and the Tennessee and Ohio valleys can see more rain and snow than in a typical winter.

La Niña can also lead to a more severe Atlantic hurricane season, which we're already seeing this year.

The main thing that forecasters stress is that while La Niña events are associated with certain climate patterns — namely, deviations in temperature and rainfall in different parts of the country — they're a matter of "probability, not certainty."

So if you're wondering whether La Niña will affect your home this winter, NOAA scientists offer this answer:

"Maybe. Probably. Probably not. The answer depends on many factors, including where you live, how strong the event continues to be, and other climate patterns that develop and influence the seasonal outcome."

What about weather events such as snow, flooding and tornadoes?

Snow is hard to predict, but experts say La Niña could bring increased snowfall over the Northwest, northern Rockies and Upper Midwest Great Lakes region. Parts of the Southwest, central-southern Plains and mid-Atlantic are likely to see less than usual.

La Niña generally contributes to more Atlantic hurricanes but fewer in the eastern and central Pacific (El Niño is the opposite). As NOAA explains, those Atlantic hurricanes form in the deep tropics from African easterly waves, so are more likely to become major hurricanes that could hit the Caribbean and United States.

The position of the jet stream also appears to have an impact on tornadoes and which parts of the country are more likely to experience them. During La Niña winters, the jet stream and severe weather are likely to be farther north.

La Niña could also worsen California's ongoing drought and make its wildfire season even more of a threat. As Bloomberg explains, the state usually gets most of its annual water from rain and snow between November and April — the same period when La Niña is predicted to shift storm tracks north and away from the region that needs it.

NOAA says drought conditions are expected to persist and develop in the Southwest and Southern Plains, while places like the Pacific Northwest, northern California and the upper Midwest are "most likely to experience drought improvement."

That's because the northern part of the country — specifically the Pacific Northwest, northern Rockies, Great Lakes and parts of the Ohio Valley and western Alaska — is likely to experience heavy rains and flooding.

How long will it last, and how often does it happen?

The National Ocean Service says that episodes of El Niño and La Niña typically last nine to 12 months but can sometimes stretch for years.

They both tend to develop during the spring, reach peak intensity during the late fall or winter and then weaken during the spring or summer.

In other words, La Niña's influence on the U.S. will be strongest between January and March but could linger into the early spring.

Why is it called that?

As the backstory goes, South American fishermen had long observed warmer-than-normal coastal Pacific Ocean waters and dramatic decreases in fish catch happening around Christmastime. They nicknamed that phenomenon El Niño — Spanish for "little boy" — after baby Jesus.

So when scientists discovered the opposite phase of El Niño in the 1980s, they decided to call it La Niña. (Of course, language about gender identity and expression is a lot more nuanced these days.)

How does this relate to climate change?

It's too soon for scientists to say exactly how a warmer world would affect the ENSO cycle.

"But remember, just because we do not have high confidence on how ENSO might change in the future does not mean that it won't," NOAA stated in a 2016 blog post. "It just means scientists have more work to do."

They are confident, however, that ENSO itself will continue into the future. And they say global warming will likely affect the impacts of La Niña, including extreme weather events.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.