It was his freshman year.

The University of Florida student had just returned from a night out drinking with friends in 2018 when he was caught by university police with a fake ID — one he said he wasn’t even using that night.

His friends had bought him alcohol, but he drank too much and fell asleep in the common area of Rawlings Hall, where his friend lived. A University Police Department officer searched his wallet, he said, and discovered his fake ID. He remembered being told he might get an email from the university and that otherwise he was “good to go.”

Two months later, his parents received a letter in the mail from the Alachua County Clerk of Court. The fake ID he’d obtained for less than $100 would ultimately cost him about $2,500 — most of which was paid to an attorney.

“I wasn’t really doing anything other than sleeping,” he said. “They kind of seemed deceptive towards me, telling me that everything’s fine. Then they slapped me with a felony.”

This is just one UF student’s story of getting busted with a fake ID, a college rite of passage that quickly evolved into thousands of dollars in legal fees.

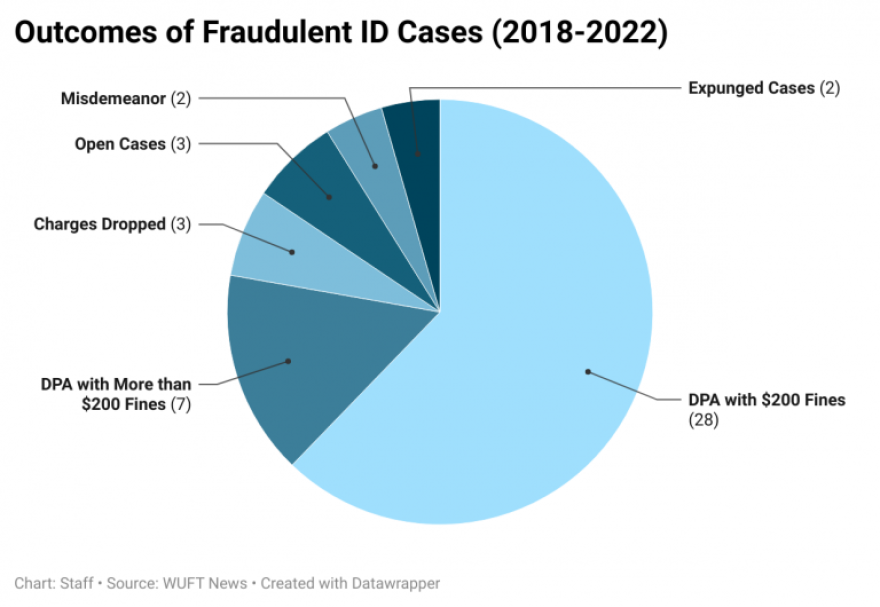

UF police have forwarded nearly four-dozen felony complaints to state prosecutors against students caught with fake IDs over the past four years, according to an analysis of court records conducted by reporting students at UF. Outcomes varied, but of the 45 total cases analyzed, all charges were either dropped or reduced to misdemeanors.

While the majority of students entered deferred prosecution deals, three students had their charges dismissed, and three cases have yet to be adjudicated — two with unexecuted summons and one that remains open. Only two cases resulted in criminal convictions — both misdemeanors — one of which had adjudication withheld. Two cases have since been expunged.

Of the 43 students contacted for this story, four agreed to interviews under the condition of anonymity. An additional four students have been handed felony complaints for fraudulent IDs in the past two weeks.

Despite being issued a felony complaint by UPD, the aforementioned student was later formally charged by prosecutors with a lesser misdemeanor and eventually offered a deferred prosecution agreement requiring him to pay $270 in legal fees as well as make a $100 donation to a local charity, according to court records.

Of the 45 defendants, 35 have entered deferred prosecution agreements.

Adam Stout, a criminal defense attorney in Gainesville, said deferred prosecution agreements are a contract between a defendant and the State Attorney’s Office. The State Attorney’s Office agrees to dismiss all charges as long as the defendant completes a list of conditions within a certain time period.

In fraudulent ID cases, this usually means paying $100 in prosecution fees and either paying $100 to a local charity or completing 10 hours of community service. After four months of good behavior, the charges are dismissed. Of the cases analyzed, 28 students agreed to this specific arrangement. Seven others received less lenient deals, paying more and/or waiting longer to get their charges dropped.

Stout said DPAs provide the two best benefits for students in these cases: rehabilitation and a punishment that will not impact them for the remainder of their lives.

He said the purpose is to give first-time offenders an opportunity to right their wrongs.

“Once you get caught in the criminal justice system, it’s very, very hard to get out,” Stout said.

As to why students caught with fake identifications aren’t initially cited for misdemeanors, UPD Captain Kristin Sasser said the charges levied in these cases more often than not meet the statutory requirements for a felony. A misdemeanor complaint would only apply if the date of birth is altered on a legitimate government-issued driver’s license. Felony charges result when the ID itself is deemed fraudulent, which is often the case among students.

Websites like FakeYourDrank and IDGOD, which some students identified using to obtain their fake driver’s licenses, offer phony licenses with altered dates of birth. But they also fill in false information for document numbers, addresses and issue and expiration dates, making ownership a felony.

“We are the administrators of the law,” Sasser said. “We don’t create the law.”

Sasser said it’s not up to the police to dictate the severity of criminal charges, and whether the State Attorney’s Office chooses to throw out a case, convict or offer a deferred prosecution agreement is up to prosecutors.

Another student interviewed hadn’t been on campus but two weeks before he experienced a run-in with UPD. Less than a month into his first summer semester, he took an Uber back to his dorm from a nearby bar. In the short walk from the car to his dorm room in Springs Residential Complex, he dropped his keys and wallet.

Police, at the complex on an unrelated matter, found the student’s black leather wallet on the ground with a fake ID inside.

After his roommates responded to a slew of missed calls from UPD to his phone, officers finally entered the freshman’s dorm room, the fake ID clipped to one of their vests. Two weeks later, the summons was delivered to his parents’ home, an unwelcome surprise setting a court date for their son. By this point, prosecutors had reduced UPD’s felony recommendation to a misdemeanor.

He called a lawyer who said he could settle the situation completely out of court and promised a DPA — for $1,500. Instead of doling out the money, he called the State Attorney’s Office himself.

“I asked them straight up if I qualified for deferred prosecution, and they told me yes,” he said. “I basically did what the lawyer was going to do for $1,500 for free.”

Four months of good behavior and $200 in fees and charitable contributions later, the charge was wiped from his record — no lawyer or court date required.

“On the legal side of things,” he said, “I did get lucky.”

To stay in good standing with the university, he visited the Dean of Students Office to go over the police report. He attended a seminar related to drugs, alcohol and the law, a punishment he thought was “pretty lax.”

Nearly a third of the students were able to secure lenient deals without an attorney. However, Stout said hiring a private attorney raises students’ chances of securing an agreeable outcome.

Whenever someone is arrested for committing a crime, the prosecutor assigned to the case will most likely not see it for a couple of weeks as support staff build a file and send out subpoenas.

With his clients, Stout said he works on building what he calls mitigation during this time, a list of documented, justified and legitimate reasons why someone should be treated differently under similar circumstances.

Within the first week, he reaches out to the prosecutor before they’ve had an opportunity to speak to anyone. The goal, Stout said, is to get their clients the best deal: a deferred prosecution agreement.

“That kind of forceful advocacy is needed,” Stout said.

Criminal defense attorneys usually charge a minimum of several thousand dollars for those facing felony charges, Stout said.

After a night out with friends at bars along the northern edge of campus, another student said he was intoxicated when he was stopped by a UPD officer for jaywalking. At first, the officer told him he would receive a fine for crossing the road illegally but soon asked if he had a fake ID.

The student said the officer threatened to search him for any fake IDs if he didn’t comply. Not wanting to risk greater consequences, he revealed his fake ID to the officer. His roommate, who chose to walk away, didn’t face any repercussions.

“I was obviously completely upset because I know a lot of people know that people have fakes in college,” the student said. “We know it’s a felony, but it’s just a part of the culture and the partying here at UF.”

The student said he was left on a cliffhanger after the police officer told him he would eventually get something in the mail. After walking away, he rejoined his friends who consoled him.

“I was just like, ‘Why me? Why am I the one that’s getting screwed over right now?’” the student said.

Days after the incident, the student tried to focus on school, but it was hanging over his head.

“It was completely taking over my life,” he said. “I was like, ‘Oh God, am I going to go to jail?’”

About a week later, he received an email from UF’s Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution about a conduct meeting. After the meeting, the student had to write an essay for the university. He submitted roughly 1,000 words about what he learned concerning the repercussions of owning a fake ID.

“It was ultimately good for growing and just learning more about the law and what goes into it and also how to handle those situations,” he said.

After telling his parents, the student said they were disappointed and worried for his well-being, especially if he would be expelled from UF. Students need to know the consequences of getting a fake ID, he said.

“Just realize that your time will eventually come,” the student said. “There’s no reason to ruin your whole life … just drinking out with your friends.”

When law enforcement reports student possession of a fake ID to the university, The Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution follows the conduct process to learn more about what happened, to educate and to possibly put sanctions in place based on university policies, according to a statement from UF.

After law enforcement completes a report, the spokesperson wrote it can be shared with Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution and is forwarded to the State Attorney’s Office. The sanctions and outcomes vary and may be decided through the student conduct process.

“There’s only one decision-maker here when it comes to all of this,” Stout said. “It’s not UFPD. It’s not the university. It’s the State Attorney’s Office because they get to make those judgment calls.”

Stout said he believes law enforcement and the State Attorney’s Office are approaching this issue correctly, as most cases end with a deferred prosecution agreement.

“This is just one of those areas where I think they get it right, ” he said.

Darry Lloyd, the spokesperson for the State Attorney’s Office for the Eighth Judicial Court, said the statute for fake IDs is written not to be malicious toward students but to effectively punish those who manufacture and sell fake IDs, as well as those committing identity theft.

Lloyd agrees a deferred prosecution agreement is the best outcome for them given the situation.

“It’s meant to be a slap on the wrist,” Lloyd said. “They did the crime and that’s our way of telling them not to do it again without convicting them of a felony.”

To see if individuals qualify for a DPA, Lloyd said a team of attorneys at the SAO screen many people being charged with lesser crimes, taking into account prior criminal history, the circumstances of their case and whether offenses were violent. If eligible, the office sends a letter to the defendant about a potential deferred prosecution agreement.

While some defendants are offered DPAs before an attorney gets involved, there’s no guarantee one will be offered at all.

Lloyd said state attorneys use deferred prosecution agreements to avoid clogging the court with petty crimes.

However, while those who go through with a DPA aren’t convicted of a misdemeanor, the fact they’ve been charged with one will nevertheless stick to their record. Many employers now require employees to disclose whether they’ve been charged with a crime, potentially hampering their ability to find work.

Former defendants can request that their case files be expunged, but the application process is lengthy and causes applicants to incur additional expenses.

Another student interviewed for this project — a UF freshman at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 — was booked into the county jail for possessing a fake ID he’d received in high school.

The student said he knows plenty of other underage students in Gainesville with fake IDs, many of whom have had similar run-ins with cops which didn’t result in a criminal complaint. The way he sees it, he was just unlucky.

Of the 45 students identified for this story, 34 are males.

Charged by prosecutors with a misdemeanor, he entered a deferred prosecution agreement and paid $200 in fees.

Because of this incident, along with other common challenges associated with the pandemic, he moved back home with his parents and transferred schools.

“I understand the reason for the law,” he said. “It’s not made specifically for the college students who are getting in trouble. It’s just a side effect that we have to deal with.”

This story was produced as an advanced reporting project by the following University of Florida students: Jonathan Acosta, Juliana Ferrie, Alan Halaly, Jiselle Lee, Meghan McGlone, Veronica Nocera, Camila Pereira and Bryce Schuele.