Elementary schools that immerse children in a foreign language are on the rise across the country. At a new French immersion school in St. Petersburg, which opened in September, American kids as young as three are learning French by speaking it all day.

From the moment the children walk in at 8:30 am, until the end of the day at 3, French is the language of the day.

Joe Barry enrolled his seven-year-old son, Jonathan in the school when it opened in September 2018. Barry speaks some Spanish, and his wife speaks French.

He says there were a few days that were tough, early on, when his son would come home and say he didn't understand what the teacher was saying.

But now?

"He's singing in French. He is saying certain words in French and I'm already encountering occasions where my wife and son are conversing and I don't know what's going on and I feel left out."

Schools like this are becoming increasingly common. According to the Center for Applied Linguistics in Washington, in 1971 there were just three of them. There were 448, at last count in 2011.

The school was founded by a Frenchman, Willy Le Bihan, and his American wife, Beth. For the past two decades, they have run a similar French immersion school in Maine.

Willy LeBihan says most focus on elementary and middle school age kids, because that's when language is most easily learned.

"There is a window of opportunity from birth to age 10-11-12 to really learn a second language easily with no effort, in context, with no accent," he said.

Even if the parents don't speak French themselves, Beth LeBihan says they often want their children to have a global view.

"In America we are starting to recognize that the world is becoming a smaller place in the sense that being able to communicate with someone in another country in another language is something that we need to embrace."

Some immersion schools are public. This one is private. Its fees range from $9,000 to $13,000 per year.

The class sizes are small. For now, just 11 children -- aged three to nine -- are enrolled. There is room for 100, eventually.

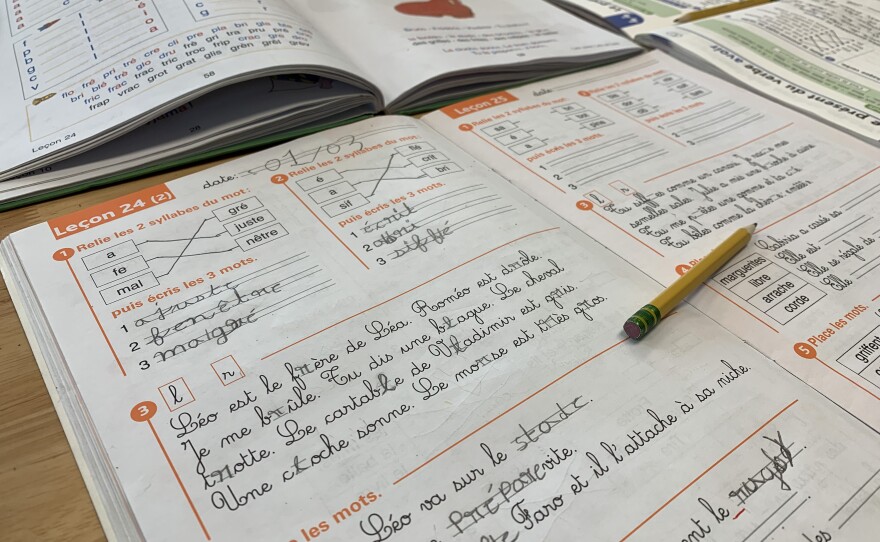

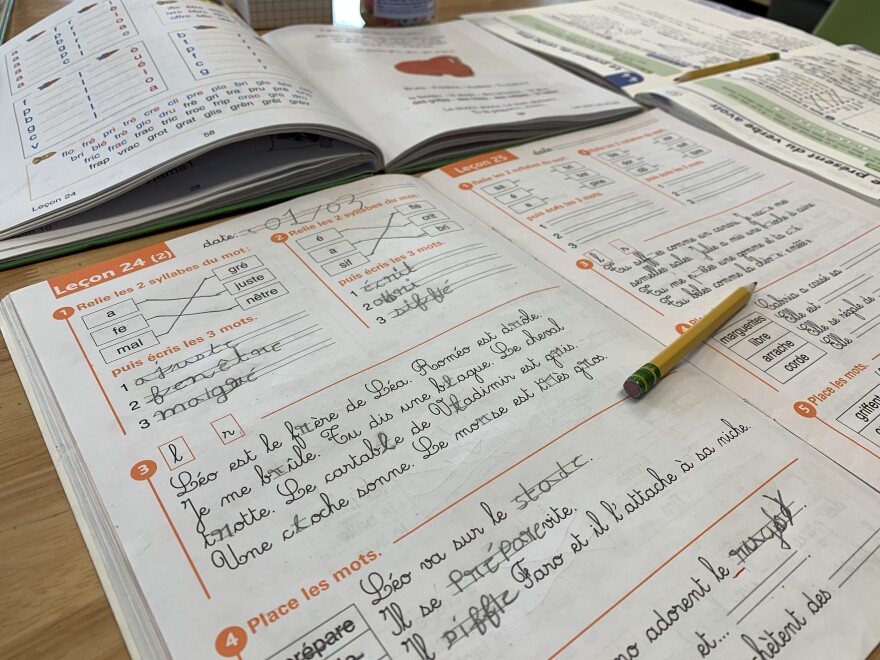

What many American schools cut back on, the French school embraces. Kids here learn to write in cursive. Music and art are key parts of the curriculum.

Unlike in many US elementary schools, they don't assign homework to the children here.

Music is the only subject taught in English. The school offers the Suzuki program, whereby children learn the piano and violin by listening and learning first. Reading music comes later.

According to Robin Harvey, who teaches multicultural and multingual studies at New York University, bilingual education has many benefits.

"Your child will come out with is knowledge of another language, knowledge of another culture, increased empathy, increased knowledge of the world, and all those things are really valuable," Harvey said.

Some experts say that knowing two languages, or more, can even improve a person's ability to focus, concentrate, manage complex tasks -- skills known in brain science as "executive function."

"Those executive functions are enhanced in bilinguals because they are used all the time to manage attention to two languages. So it makes performance easier. It doesn't make you smarter. It doesn't add IQ points," said Ellen Bialystok, a distinguished research professor of psychology at York University in Canada.

But, Bialystok says, the benefits can extend long beyond the school years, into old age. Some studies show that being fluent in two languages may even protect against, or delay the onset of dementia.