At the Mulberry Community Academy in Polk County, children learn in Spanish and English.

The kindergarten class repeat after their teacher, who introduces them to the sounds of the Spanish alphabet.

"We are language first. Before they even write the letter, they're hearing it, saying it, drawing it, and then they're writing it," explained Sara Garcia, an ESE teacher at the school.

After this class, the students will switch over to math, which is taught in English.

The dual-language school is run by the non-profit Redlands Christian Migrant Association (RCMA), which operates several charter schools and child development centers across the state. They primarily serve children of migrant farmworkers, most of whom speak Spanish at home.

"We're not only working with the child, we're working with the family," said Isabel Garcia, RMCA's executive director.

Garcia said there's a huge need for schools that prioritize the kids' culture while also accommodating the families' seasonal schedule.

Migrant farmworker families have to follow the harvest, she said.

“So they pack everything they have into their vehicle and they move to North Carolina, where they're going to either pick tomatoes, or they go to Alabama, where they're going to pick tomatoes, or they go to New York, where they're going to pick apples," said Garcia.

Often, children travel with their parents and other relatives. They leave before one school year is over and come back after the new year has already started.

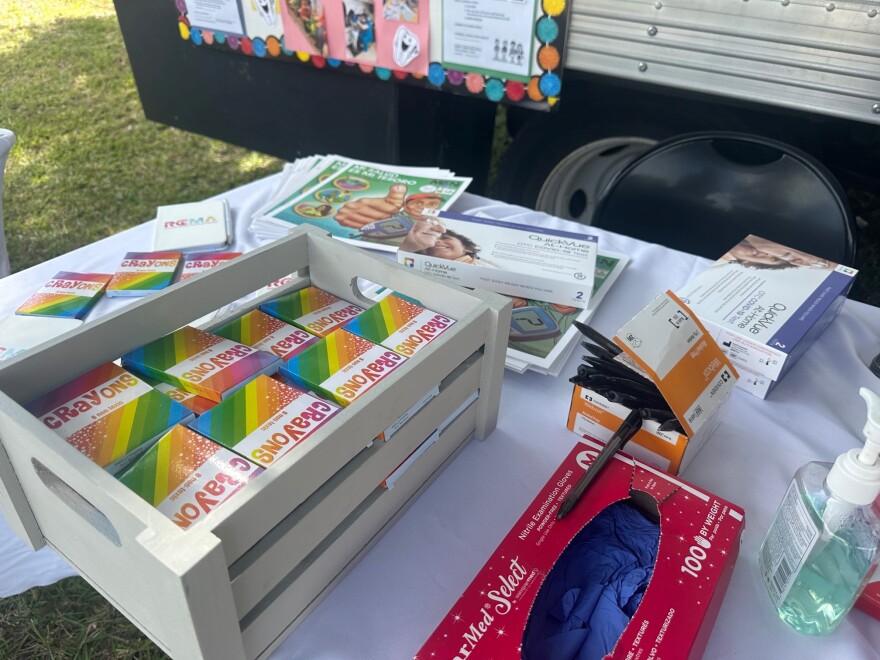

"What migrant children need is...that catch-up, and in order to do that, RCMA goes above and beyond by providing wraparound services," said Garcia.

That can look like extra tutoring or weekend classes to ensure students are prepared for state exams.

Some farmworker families feel impact of immigration bill

Support for families is more crucial than ever this year, said Garcia.

Senate Bill 1718, which became law in May, makes it illegal to transport undocumented individuals into the state.

Between 150,000 to 200,000 seasonal and migrant farm workers travel into Florida each year. According to the Florida Policy Institute, about 47% of agricultural and related workers in Florida lack documented immigration status.

Other sections of the bill include requiring employers with more than 25 employees to use the federal E-Verify system to ensure those hired after July 1 are documented.

The law also requires hospitals that accept Medicaid to ask admitted patients and emergency room visitors their immigration status. However, patients can decline to share their immigration status.

Immigrant advocate groups such as the ACLU have called the sweeping bill "draconian" and said it "makes it harder for immigrants to provide for their families."

Garcia said the law has directly impacted some of the families they serve.

"During the summer, we ran some summer programs to be able to serve some of the children that we knew that will normally leave, who didn't leave," Garcia said.

"Our families are living in fear. Our families don't know if they're going to leave because they are scared that when they do come back in October and November, they will be detained and convicted of a felony for transporting their own family."

Expansion will continue to aid growing immigrant population

With some families staying in Florida and a continuing need for those dual-language and wraparound services, the Mulberry charter school is planning to expand.

In the next five years, the school intends to add grades two through eight, so that students can continue through and graduate middle school like they do at RCMA's charter schools in Immokalee and Wimauma.

There's already a growing waitlist for those spots.

"We're fully enrolled, the need is obviously here," said Garcia.

About $14 million is needed for the construction of a new building that will serve the additional grade levels.

Ilda Martinez, an RCMA alumni who now works in Washington D.C. with the National Migrant and Seasonal Head Start Association, recalled her own experience traveling with her farmworker family.

She remembers driving across the country to Michigan for apple season, reading most of the way.

"It kind of felt like I was traveling with my whole family," said Martinez, "And I really enjoyed it. I was like, 'Oh, I've been to this state. I've been here.'"

But things are different now, she said. There's greater risk in such travel and she hears that some family and friends don’t want to return to Florida.

"Just seeing that and hearing that, it was a little terrifying, I think, and a little heartbreaking."

But even with so much uncertainty, Martinez said, the community remains resilient. She sees the support for Mulberry Community Academy's expansion.

"I think, when it comes to moments like this, the community, instead of falling apart, it comes together," she said.

Between that and the work she's doing in D.C., Martinez sees people working to help this community.

She said this gives her hope that migrant farmer families, regardless of their documentation status, can still thrive in Florida.