Divers were busy in early April transplanting coral grown in the Tampa Bay area to stressed-out reefs in South Florida and The Florida Keys. This unprecedented effort revolves around genetics.

Florida's once-colorful coral reefs are under siege. Warming seas, ocean acidification and diseases like coral bleaching are leaving parts of the world's third-largest reef a ghostly white.

Now, there's a new threat - Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease. Or more simply, White Plague.

The Florida Aquarium may have an answer.

In early April, divers transplanted about 3,000 tiny Staghorn corals throughout the reef, where they'll be glued to existing coral beds. But these aren't just any staghorns.

"It is the largest outplanting of genetically diverse Staghorn coral ever in the history of Florida," said Roger Germann, CEO of the Florida Aquarium. The aquarium is giving the reef a little genetic diversity. They've scoured reefs throughout the world for a variety of staghorns, trying to find ones that can withstand the onslaught of White Plague.

The disease was first detected in 2015 off of Broward County, and has since been found throughout the Keys. It's an infections bacteria that eats away at the coral. Germann says it may have spread to the Bahamas and Costa Rica, carried by boats and ballast water.

In the past, coral reefs have been bolstered by simply breaking off pieces of healthy coral and transplanting it. But Germann says those corals could be struck again by the White Plague.

"So if you diversity the genetics, and you have this gene pool, what you're hoping for is to get coral that might be more resilient to the pressures that are out there, and have a longer-term chance," he said.

First, a little "birds and the bees" about these marine invertebrates. They only mate once a year. So divers have to figure out what time boy corals release sperm and girls release eggs and scoop them out of the water. Then, they're transported to "Coral Ark" in Apollo Beach, where they're attached to concrete tiles. There, the toddlers eventually blossom into teens.

"So what we are doing is "arking" - in essence, like Noah. trying to ark the coral, just to protect it and save it," Germann said. "We are learning how to grow it for the eventual put-back into the wild."

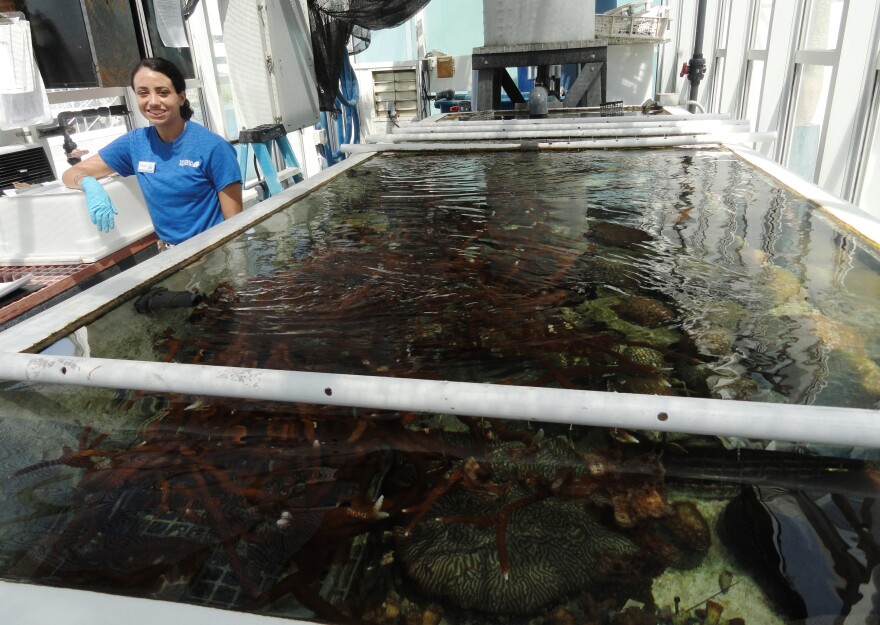

On the rooftop of the Florida Aquarium, in the shadow of downtown Tampa's skyscrapers, as far removed as you could imagine from the quiet of a submerged reef, the steady hum of a filter keeps cool water flowing through one of those "arks."Here, a greenhouse basks in the sun, keeping temperatures in the toasty 90's. After all, they're trying to mimic their natural environment.

Gabby Vaillancourt, is a senior at the University of Tampa, majoring in marine science. The intern keeps her cool by standing in front of a window air conditioner. She's tending to various forms of coral that are suspended from hangars in the water stream.

Tiny "frags," or fragments of genetically-selected corals, dangle in the artificial current from white plastic hangers called coral trees.

"And so they're hanging down," Vaillancourt said. "And this orientation helps them grow ten times faster in here than in the wild, so they can grow, I believe a year in here, and then they can send those pieces back out to be planted in other coral trees out in the wild."

So while all of this is still considered experimental, Germann sees some light at the end of the White Plague's tunnel.

"We've only seen breakthroughs within the last year or two that we are sharing with the world that has shown our success," he said. "Three years ago, we did the same thing with the spawn, and had no success at all. So our scientists are working, they're dialing it in, but now we're starting to see that success, which is why we're optimistic about saving this reef."

So for now, it may be the best chance for Florida's reefs to be able to last through the 21st Century.