By Cathy Carter

It's just after sunrise on Sarasota's Lido Beach and the start of sea turtle patrol for Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium Senior Biologist Melissa Bernhard.

“We have a report of a possible nest a couple hundred feet down,” she said on a recent morning. ”We're just going to walk down to it and see if it is a nest and take some data on it, regardless."

It’s common this time of year to see wooden stakes blocking off sea turtle nests on area beaches.

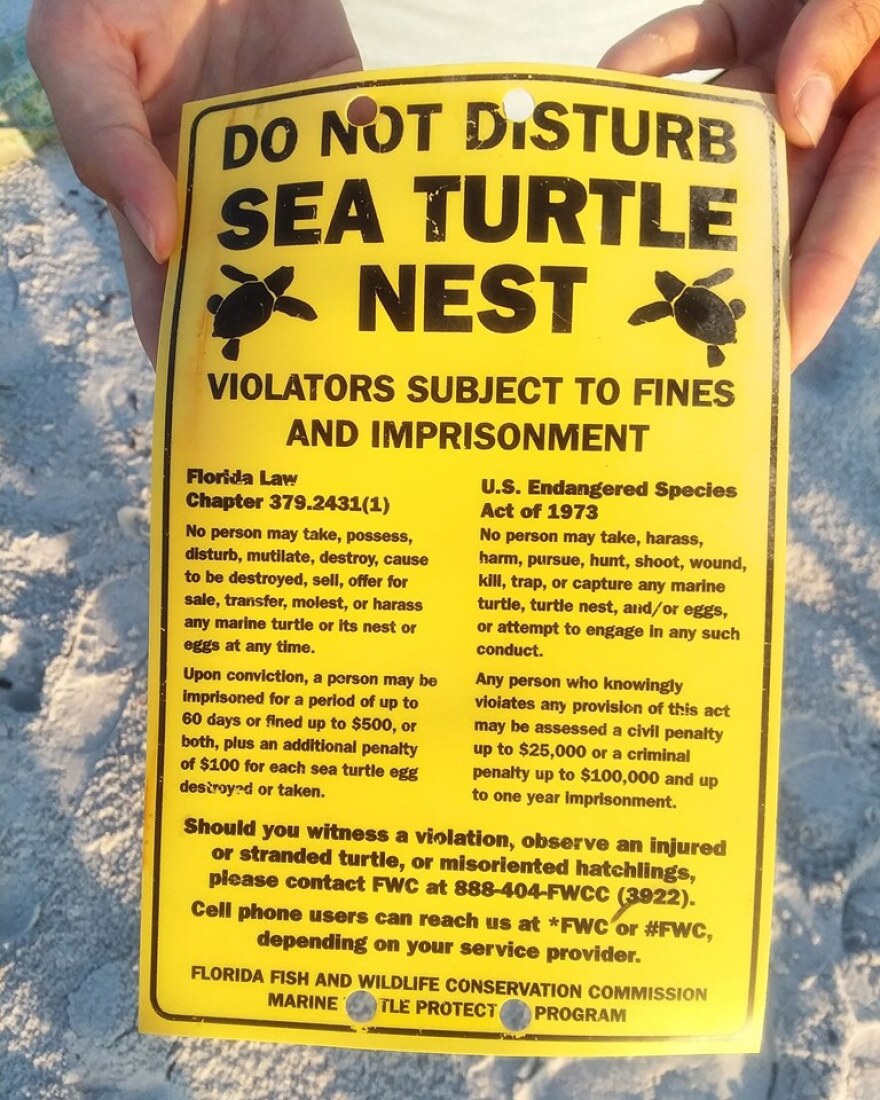

Nest marking materials are protected under the U. S. Endangered Species Act and Florida State Law. Bernhard says nesting numbers have grown over the past decade but sea turtles still face a host of obstacles.

"We're losing a lot of habitat which is critical for their nesting,” she said. “With global warming there's a whole, ‘how is that going to affect these temperature-dependent animals.’ So I think there's still going to be a lot of caution even though the numbers seem to be increasing."

Indeed, despite the ravages of red tide, sea turtles created a near-record number of nests last year on the 35-mile stretch of beach that Mote scientists and volunteers have monitored for nearly 40 years.

Sarasota County has the highest density of loggerhead sea turtle nests on the Gulf of Mexico. But on this recent morning, the reported nest is what’s called a "false crawl." That's when a female sea turtle heads back to the water without nesting.

"The track is continuous throughout,” Bernhard observed. “A nest involves her disguising it by throwing sand over it so it leaves a small mound where the track is no longer visible cause she's covered it up."

Most female sea turtles return to the same beach year after year, crawling out of the water at nighttime to dig with their flippers and then laying about 100 eggs.

Bernhard says there may be any number of reasons why this turtle decided not to nest.

"She could have crawled up and said 'oh this sand isn't what I want it to be.' I'm anthropomorphizing but something along those lines, or she could have been threatened by something, lights, or a person or a predator, potentially."

Even with the challenges of beach erosion, pollution and coastal development, Mote staff discovered almost a dozen nests before the season officially began in May. That's the highest number recorded since Mote began tracking sea turtle nests.

That's a good sign for the marine reptiles, especially after last year’s red tide killed off hundreds of turtles and other marine life.

Bernhard believes the 16-month toxic algal bloom should not be a factor for this year's nesting season.

"Most of the stranding’s that we were seeing in our area from the red tide were of the juvenile stage,” she said. “Hatchlings and nesting females are not eating near shore as much as those juveniles who are getting more exposure through their diet."

The 2019 season runs through October 1 and so far is on pace to surpass last year's figures.

Mote recorded more than 3,000 sea turtles nests last year. It's estimated that only one in 1,000 hatchlings make it to adulthood.