This post has been updated.

When Osvaldo Matos Ross first saw the drab pink house on a quiet cul-de-sac in Cutler Bay four years ago, he never imagined it would be his future home.

Chase Bank had foreclosed on the previous owner and the three-bedroom, three-bath house had sat empty for five years. The roof had severe damage and mold creeped up the walls and through the dated bathrooms.

READ MORE: Florida Is A Hot Spot For Government Homes Sold In Flood-Prone Areas

“It was destroyed, completely,” he said. “The first time I was here, I said I’m not going to take it.”

The seller, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, was selling it as-is. But even with the troubling roof, Matos Ross knew it was a steal at just $255,000.

“It’s worth the risk,” said Matos Ross, who has since repaired the roof, painted the house a bright yellow and added life-sized concrete lions alongside a bubbling fountain. On the surface, HUD appears to have fulfilled its mission: Matos Ross now owns a beautiful house in a market increasingly accessible only to the rich.

But according to an NPR investigation, a high number of homes sold by HUD, like the one Matos Ross purchased, are located in risky flood zones.

Nationwide, HUD sold nearly 100,000 properties in flood zones between 2017 and 2020, a disproportionately high number when compared to the total number of homes sold in the U.S. The investigation identified Florida, along with Louisiana and New Jersey, as a hotspot for such sales.

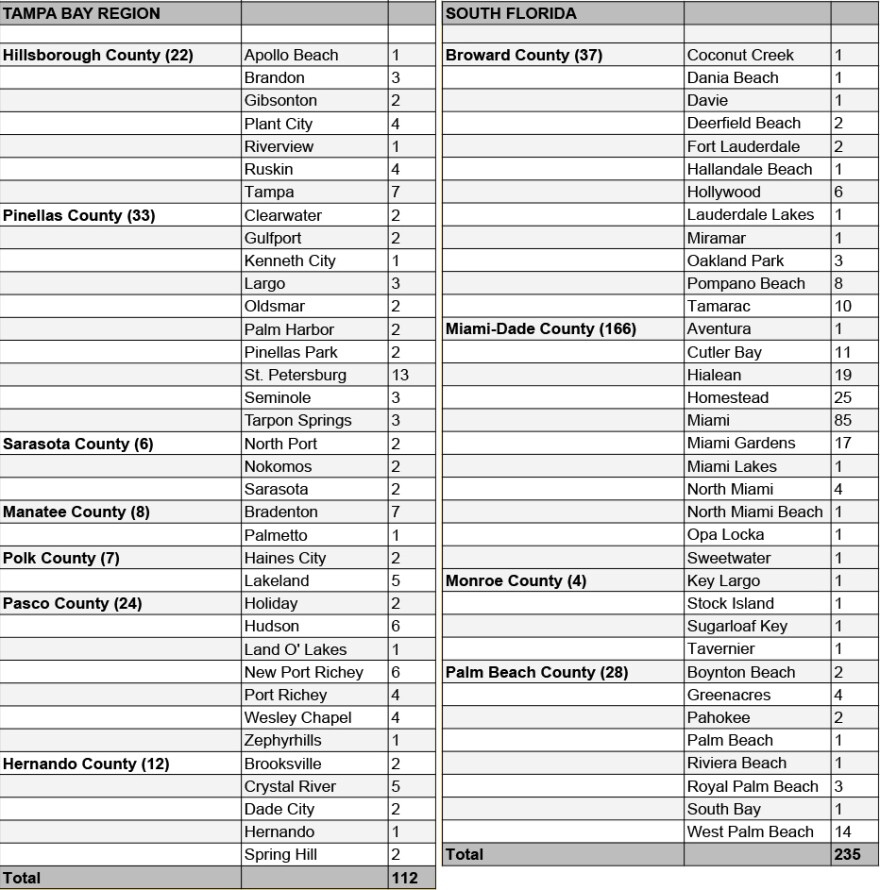

In South Florida, HUD sold more than 230 houses or condos located in flood zones. Those sales also included four properties that have suffered repeat flooding. All four are designated by the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), which administers the National Flood Insurance Program, as “repetitive loss” properties, after collecting more than $500,000 in claims since 1999.

Selling houses in such vulnerable areas, housing experts told NPR, runs counter to HUD’s mission to provide housing that’s both affordable and safe.

Such sales also appear to contradict efforts by other federal agencies working to limit damage and fight flooding. That includes a $4.6 billion plan by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to protect Miami-Dade County from storm flooding and ongoing efforts to buy out properties vulnerable to hurricanes. Two years ago, FEMA set aside $44 million to buy out hurricane-battered houses in Florida after Irma hite the state. The agency paid another $224 million in flood insurance claims after Hurricane Michael.

HUD, too, has also contributed to recovery efforts, providing more than $700 million after Michael.

But in Florida, selling distressed homes can be a lucrative business, even for HUD.

“A lot of times we have...agents tell us, I already have an offer 20, 30 or 40 percent higher than the asking price and all cash,” said Roger Pardo, a broker registered to sell HUD homes and owner of The Realty Group of Miami. “The problem now with the HUD houses is we have people with great money buying them.”

HUD acquires the homes as the insurer for federally-backed mortgages like Fannie Mae, or loans from the Veterans Administration. When banks foreclose, if the banks are unable to resell the homes, they can be returned to HUD to collect on the insurance.

In a statement sent to WLRN, a HUD spokesman said millions of homes across the country are located in flood zones, which he said can also be vibrant communities.

“We believe that we have a dual obligation to ensure that neighborhoods do not suffer from blight via long-term property vacancies, and to ensure that homebuyers have the information they need to make the decisions that are right for them when purchasing a home,” the statement said.

'I Would Never Do This Again'

But while HUD sells the properties as-is, a common phrase in real estate jargon to warn buyers, not all owners interviewed by WLRN were fully aware of the threat from flooding.

By the time he learned he needed flood insurance for his Cutler Bay house, Charles Mullings said he was too far into the deal.

“I think I signed for the house even before I knew it was a flood zone,” he said.

Mullings has lived in South Florida for more than four decades, so was not all that surprised to learn the house was in a flood zone. But as he’s struggled to renovate and keep up with repairs on the 33-year-old house, he said he wished he’d known in advance about the additional cost for flood insurance.

“Maybe I wouldn’t be here,” he said. “I love the house, I love the layout of the house, the master bedroom is awesome. But I would never do this again.”

Jean Ronald and Madeleine Moise closed on the West Palm Beach house they share with three teen-aged children last year. They spotted a "for sale" sign in front of the house and contacted the realtor, but say they never discussed flooding risks and now worry they may be unprepared. They have insurance, but say they’re unsure about what that exactly covers.

We “don’t have any experiences about floods,” Madeleine Moise said.

Flood risks can extend to renters as well, whose landlords purchase HUD homes as an affordable investment.

For the last eight months, Erick Chy has rented a house on Fillmore Street in Hollywood that his landlord purchased from HUD in 2017. Despite the frequent puddling in his yard, Chy was surprised to hear he was renting in a floodplain.

"When there is rain, the water comes in," he said, indicating water comes up a few inches high in the middle of his front yard.

Buyers Know The The Risk, But Still Take The Leap

In reality, as flooding problems worsen across South Florida, many affordable areas will be in flood zones. Already, nearly all of Doral, West Kendall, Sweetwater, Homestead, Cutler Bay and Florida City already lie in flood zones.

For many of his clients, Pardo, the broker, said these homes are often all they can afford.

“We have teachers, we have employees at the restaurant, employees at the bar. And they want to live close to where they work, especially when they have kids to get to school,” he said. They want “to have a real life.”

In Florida’s competitive market, buyers are often competing against more deep-pocketed investors, he said.

Pardo, who is originally from France and often works with overseas buyers, said many are also willing to pay cash.

“They pay cash, so there is no mortgage,” he said.

And the risks from flooding?

“They all know,” he said. “In France, when I meet people that I know in France, they always tell me, so are you under the water?”

To meet its mission to supply affordable housing, HUD is supposed to offer its properties first to local governments or non-profits and then owners who plan to live in the properties. Investors are supposed to be among the last to bid. But how carefully that rule is enforced is unclear.

“They all know [the flooding risk]. In France, when I meet people that I know in France, they always tell me, 'so are you under the water?'”Roger Pardo, broker and owner of The Realty Group of Miami

In a response to WLRN, HUD’s press office sent a statement saying the agency was working to increase the number of properties available to owner-occupants.

“If the property is not sold within a certain period of time based on the insurability of the property to an owner-occupant, the properties become available for sale to the general public, including investors,” the statement said.

HUD did not respond to a question asking how long properties could be listed before before they can be purchased by investors.

South Florida is no stranger to selling swampy land, which also may account for the large number of homes in flood zones. With nearly a thousand new residents arriving each day, it’s also easy to forget its long history with flooding.

Alain Leyva bought his three-bedroom, two-bath house from HUD two years ago in the Lakes By the Bay neighborhood not far from Mullings and Matos Ross. The house is one of hundreds built by Lennar, Florida’s biggest home builder, on wetlands and old farm fields in South Dade.

Leyva’s one-story house sits just four houses down from Glossy Ibis Lake, one of the neighborhood's big lakes dug to provide fill on which to build houses and roads. The lakes, including Short-billed Dowitcher Lake and White Ibis Lake, were named for the birds that once inhabited the wetlands.

Three decades ago, Lakes By the Bay was one of the hardest hit when Hurricane Andrew plowed ashore just a few miles to the north, with a storm surge that nearly topped 17 feet. Residents sued Lennar, claiming shoddy construction allowed much of the damage. Lennar settled, paying each owners almost $7,000.

After a typical summer rain one afternoon this week, the road to Leyva’s house was partly flooded, forcing cars to swerve into the opposite lane.

But Leyva doesn’t consider flooding a significant threat. Working with HUD as the seller was “not easy but not complicated,” he said.

While they represent a fraction of the houses sold, the properties that suffer repeat flooding are among the riskiest. On its website, FEMA says it closely monitors such properties to find ways to reduce the cost from damage.

The four properties WLRN identified include a condominium in Edgewater; an apartment in a gated community alongside Blue Lagoon near Miami International Airport; and a house in South Miami Heights.

The properties, records show, also include a mobile home at a Homestead trailer park, one of nine mobile homes in the park HUD sold near the Everglades.

A risky mobile home was especially alarming for Adrian Madriz, the executive director of Struggle for Miami's Affordable and Sustainable Housing (SMASH), a nonprofit working on South Florida’s housing shortage.

“The fact that they think it’s even okay to sell those mobile homes to poor people so that they can concentrate their lives in a very dangerous area when it comes to sea level rise and climate change — that to me by itself seems incredibly unjust,” he said.

The house Matos Ross bought sits in FEMA’s riskiest flood zone, with a 26% chance of flooding during the life of his 30-year mortgage. But the fixer-upper enthusiast said that doesn’t really bother him. He said he hasn’t experienced much flooding since he moved in. And, he said, the value has nearly doubled to more than $400,000.

He worries about sea rise, because his city straddles Biscayne Bay, he said, but not too much.

“I think it's going to be for the next generation,” he said, “the one that's after me.”

Copyright 2021 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM.