Welcome to Arcadia, population around 8,000. It's the heart of — and only real city — in DeSoto County, a farming and ranching center that hearkens back to Old Florida. It's home to an historic downtown that got battered by Hurricane Charley in 2004, and Florida’s largest rodeo, anchored in a building named for the very company that wants to dig the state's newest phosphate mine.

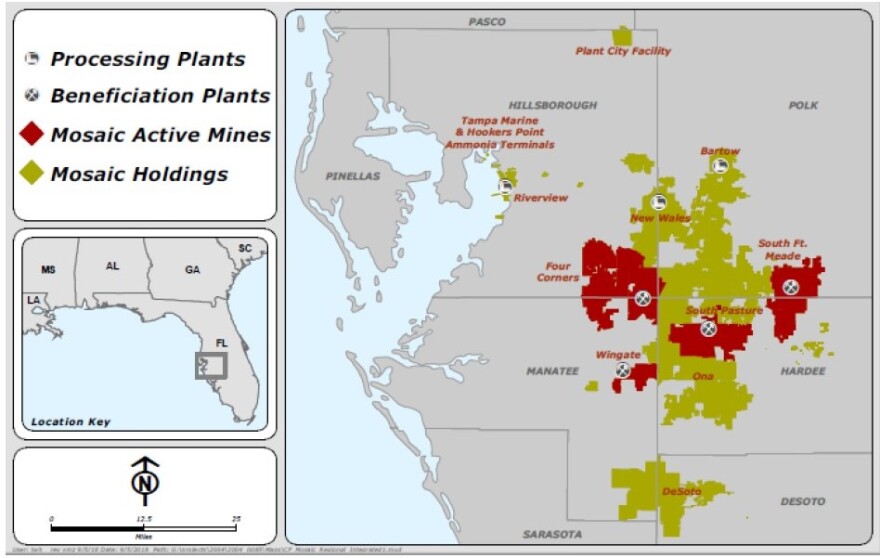

Mosaic got a rare rebuke in 2018, when DeSoto County Commissioners voted against rezoning fourteen thousand acres of ranchlands and groves in the county's northwest corner for mining. But the company — which reported sales revenues in its phosphate division of $465 million in August alone — pressed back.

The nation's largest phosphate producer went to court, and shortly after that vote, county commissioners agreed to an arbitration mediator and let Mosaic have another vote as early as 2023.

A lot of people aren't so excited by that prospect.

Opponents to the mine go far beyond NIMBY. Here, "not in my backyard" takes on a larger meaning.

"We're going to stop this chemical plant. Because it's still virgin territory and Mosaic has all these other facilities," says Tim Ritchie, an earnest man with a flowing handlebar mustache, one of the founders of March Against Mosaic.

The citizen's group has held several rallies against the mine downstream. They plan another rally at the mouth of Charlotte Harbor at the end of October.

One of their main concerns is the mine would straddle Horse Creek, which flows through mostly ranchland in Hardee and DeSoto counties. It's considered one of the purest waterways in Florida. After Horse Creek flows into the Peace River, water is siphoned to slake the thirst of tens of thousands of customers in Sarasota, Charlotte and DeSoto counties.

Mosaic spokeswoman Jackie Barron says Mosaic and it's predecessor, IMC-Agrico, have been planning this mine for two decades.

"We recognize we are an impactive industry," she said. "But we are also good steward of the environment and bring with us environmental leadership and expertise that few others have."

Barron says 9,000 acres have already been rezoned for mining. The nation's largest phosphate producer owns a total of 23,000 acres that are in areas that could be mined.

So in the meantime, the company is holding a series of public workshops on various parts of their mining plan. The next, on Nov. 2, will be in Arcadia's Turner Center — right next door to the Mosaic Rodeo Arena.

"The goal of these workshops is to educate not only the county commissioners, but the community as well," Barron said. "We want to bring operations into this community and have the community, by and large, be excited by the opportunity that it presents."

Ritchie isn't so excited. He worries about nutrients released from mining floating downstream and adding to the blue-green algae that has occasionally turned nearby rivers into pea soup.

"Do we want the Peace River and the canals in Punta Gorda looking like Cape Coral or looking like Caloosahatchee?" he asked. "No way."

Ritchie says, quite simply, that Mosaic can't be trusted. He ticks off a list of spills that devastated wildlife, including sinkholes and ruptured gypsum stack walls. And several in the Peace River pre-date Mosaic.

In 1971, two huge spills of phosphate waste — including one estimated at a billion gallons — killed every single fish around Arcadia. It was written that Charlotte Harbor turned the color of chocolate milk.

Barron says the company regularly monitors the health of both Horse Creek and the Peace River.

Still, people like Henry Kuhlman don't want to give them the chance to make that happen.

Kuhlman is a former Hardee County resident who still owns two properties there. He's with the advocacy group People for Protecting Peace River, and doesn't want to see what has happened to parts of Hardee — which is home to three Mosaic mines — be repeated in DeSoto.

"It's a cowboy county. Agriculture, small town, family oriented, farmers, horse country, Cracker land. That is one of the last places like that."

But given Mosaic's deep pockets and history of getting counties to reverse their rezoning denials, which is what happened a dozen years ago in the Altman Tract in Manatee County, Kulhman's wish may not come true.