Coming up with ways to protect Miami-Dade County from the stronger storms and higher seas of the future has generated more questions than answers over the last few years. The county’s latest concept could stir up even more controversy.

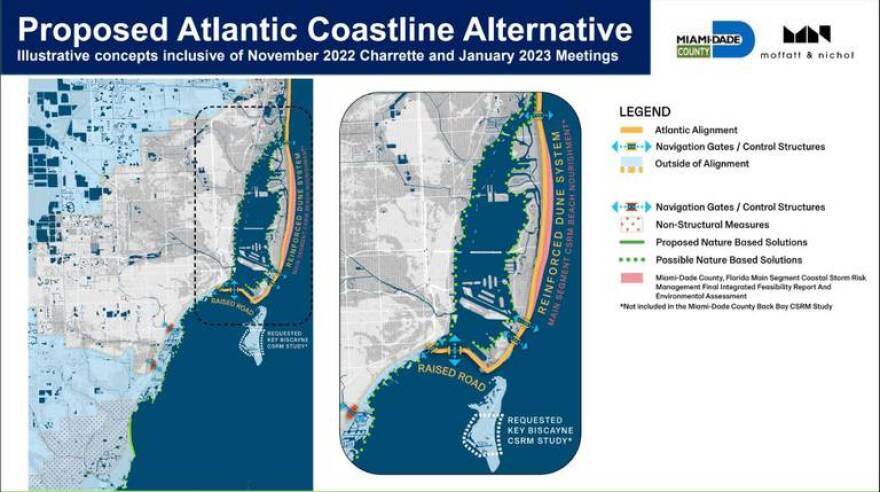

It involves closing off most of Biscayne Bay from the Atlantic Ocean with natural and man-made barriers— a stronger dune system along the beach that would tie into massive storm surge gates at major ocean inlets, including potentially blocking off most of the currently open ocean under one bridge along the Rickenbacker Causeway.

This is the county’s second go-round with the Army Corps of Engineers, which has been tasked with coming up with a comprehensive solution to a complex problem: Protect people and property in the vulnerable coastal county without breaking the bank, hurting the environment or upsetting residents. At least too many of them.

Last time, after three years of studies and public meetings, the Corps ended up suggesting a strategy that involved elevating thousands of homes, flood-proofing important buildings like fire stations and hospitals, planting more mangroves in South Dade and building a tall steel and concrete wall along the county’s coast — cutting through the bay bottom in places and cutting residential neighborhoods in half in other spots.

That last part didn’t fly. Miami-Dade rejected the plan and sent the Corps back to the drawing board, with a promise to consider more nature-based solutions and hold more public meetings for its coastal storm risk management study, also known as the back bay study.

Now, the county has some new ideas for a plan it could consider supporting and it’s asking residents to weigh in at a public meeting on Feb 23.

In a public presentation on Friday, county Chief Resilience Officer Jim Murley presented two concepts for consideration that he said appeared to be supported by the community.

“We started to see consensus on two options, two options that move us forward from where we were in 2021,” he said.

One, called the “nonstructural option” in Corps parlance, looked very similar to the final product the Corps delivered in 2021. It called for elevating thousands of homes, protecting critical buildings from floodwaters and lining the shore with natural protections like more mangroves, artificial coral reefs and beefed-up spoil islands.

The other, called the “Atlantic coastline alternative,” is more dramatic and involves another protective wall. Except this time, the proposal would push it from the mainland and instead form a ring around north Biscayne Bay. Massive storm surge gates would be installed at major openings to the Atlantic at spots like Haulover Inlet, Government Cut, Norris Cut and the Rickenbacker Causeway.

The coast of Miami Beach, which wasn’t protected under the old plan, would get higher oceanside dunes and other natural solutions to tie into the new wall system. The idea, Murley stressed, was not to build walls that block anyone’s views or beach access.

“It doesn’t mean walls in the water in front of the beach, it doesn’t mean walls behind the beach,” he said. “We would never affect the beach access. That’s off limits.”

It’s hard to know how realistic these ideas are, since Miami-Dade is years (maybe even a decade) away from implementing anything from the Corps study. In August, the county and the Corps will decide whether to even continue with the study, since neither side wants to end up with a final product that flops again.

But if the Corps and County do move forward with a potential plan to wall off north Biscayne Bay, the impacts on the environmental well-being of the already frail bay could be profound. Last time around, environmental advocates were vehemently against any structure built along the bay bottom.

Overlapping Army Corps studies

Moving potential surge barriers away from the mainland and into ocean inlets would solve several problems the county faced under the old plan. For one, it would satisfy residents outraged over losing their ocean views or worried about unequal and divisive protection running through suburban neighborhoods.

For another, it shifts the focus away from outlets like Little River that are key to the drainage system keeping South Florida dry. These canals and pumps are run by the South Florida Water Management District, and they’re already failing to keep up with the stresses of a booming population and rising sea levels.

In addition to the Back Bay study, the Army Corps is currently in the midst of another study focused on that drainage system, which will result in suggestions to improve the system, and likely, a substantial amount of cash from the federal government to actually do the work.

At the presentation, Murley mentioned that the original Back Bay plan had called for a surge barrier at the mouth of Little River, and the new re-study of the drainage system would likely involve changes to the massive pumps and flood barriers already within the river, a mere five miles away.

“We decided we need to get away from the canals, leave the canals to the district,” he said. “It seemed like we were overlapping each other and we wanted to get out of the way.”

But moving big structures like storm gates out toward the barrier island coastline is a trade-off that could result in less protection, something that Murley acknowledges. Moving them eastward would protect more parts of the county, like tiny North Bay Village, but it would likely block less water for coastal and inland areas on the mainland.

“You’re not trying to hold the water out. The storm surge is coming in. But you’re doing things that significantly reduce the loss of life,” Murley said. “If you have a structure that gives you that ultimate level of protection, we learned last time it comes with walls and pumps. And that’s a hard thing to site in an urban area.”

Corps wants input

Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava met with top brass at the Corps a few weeks back to discuss the concepts and see if they would be instantly shot down. They weren’t.

“My top priority is the safety of Miami-Dade County,” Levine Cava said in a statement. “It will be critical to find the best, most achievable path through these various plans.”

Michelle Hamor, chief of planning for the Norfolk district that’s handling the study, said the answer wasn’t an immediate no, although her agency wants to hear from local residents and activists.

“It provides a foundation for us to build from,” she said. “We need that input.”

The Corps is also working to address another Miami-Dade concern, coordination between the many different Corps studies and funded projects happening in the county simultaneously. Beyond the Back Bay study and the review of the drainage system, the Corps recently approved a plan to keep adding sand to Miami Beach for decades to come, and it’s also studying an Everglades restoration solution for south Biscayne Bay.

“We don’t want to implement a solution that will potentially decrease the benefit from other studies,” said Abbegail Preddy, project manager for the Back bay study. “We’re in coordination with those project managers and project teams.”

The next virtual public meeting on the Back Bay study will be held Thursday, February 23, 2023 at 5:00 p.m.

Register to the meeting here.

This climate report is funded in part by a collaboration of private donors, Florida International University and the Knight Foundation. The Miami Herald retains editorial control of all content. This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative formed to cover the impacts of climate change in the state.

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative formed to cover the impacts of climate change in the state.

Copyright 2023 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM.