Tampa fertilizer giant Mosaic is seeking federal approval to use an estimated 337 tons of phosphogypsum, a mildly radioactive byproduct from the company’s phosphate manufacturing process, as a test ingredient in road construction.

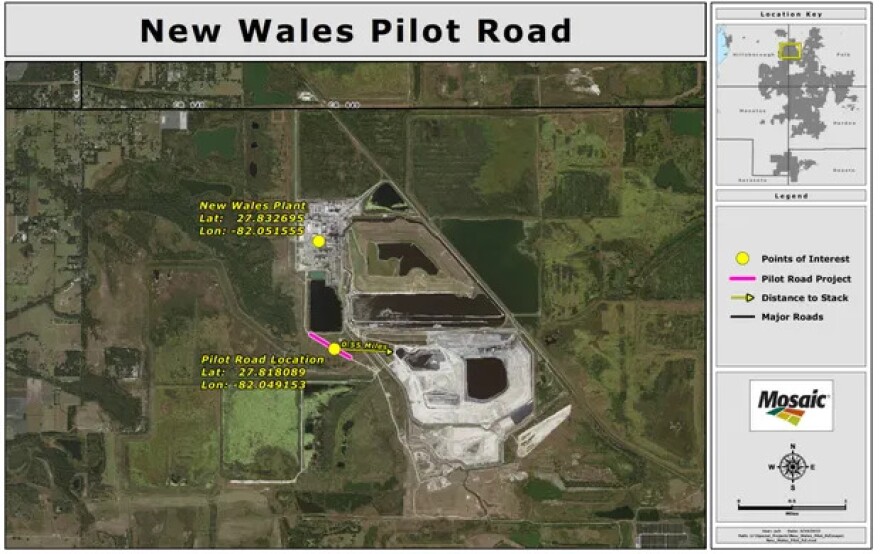

Phosphogypsum is currently stored in about two dozen “stacks” across Florida, including one at Mosaic’s New Wales plant in Mulberry. Now, the Fortune 500 company wants to remove the byproduct from its gypstack and mix it into a 1,200-foot road at the plant, according to a petition to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency obtained by the Tampa Bay Times.

Documents outlining the plan offer a first glimpse into the projected amount of phosphogypsum to be used for the study. The company’s truck drivers would haul the tons of material to the test road, roughly a half-mile from where it’s currently kept.

The phosphogypsum would be stored in a “staging area” until it’s ready to be blended with three ingredients for testing in roads: limerock, concrete and sand. Construction workers, equipped with their own personal gamma radiation detectors, would spend about a month building the test road, records show.

Mosaic described its proposed project to federal regulators as the “intermediate step between laboratory testing and full-scale implementation” of phosphogypsum in roads. For some concerned environmental groups, that’s proof the company has big plans to start building roads across the state — and maybe the nation — using the mildly radioactive byproduct. All while a new cash stream rolls in.

“The Mosaic Company has made it very clear that this is the first project in a larger campaign to use this waste in road construction,” Ragan Whitlock, an attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, wrote in a statement to the Times.

“While Florida’s Bone Valley is the front line for this waste, there are many stacks across the nation,” Whitlock said. “Mosaic’s campaign could potentially set the stage for fertilizer manufacturers from Idaho to Texas to pursue the same.”

Green light from DeSantis, Florida Legislature

New details about Mosaic’s plan, first reported by the Times last month, are emerging just weeks after Florida lawmakers and Gov. Ron DeSantis cleared a decisive path for more research on using phosphogypsum in Florida roads.

Late last month, DeSantis signed a bill that will allow the Florida Department of Transportation to study the use of phosphogypsum in road construction, defying calls from a coalition of environmental groups urging his veto.

The measure — which was dubbed the “radioactive roads” bill by critics — was lobbied by Mosaic. And in May, finance records show, the company hosted and paid nearly $25,000 for a fundraising event for the state lawmaker who sponsored the controversial bill, Rep. Lawrence McClure, R-Plant City.

If federal regulators accept Mosaic’s request, the company will turn to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection for its approval, records show.

Mosaic met with that agency two times in 2022, once on June 27 and again Aug. 18, according to email invites obtained by the Times. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection said it has no detailed records or notes from those meetings, but a spokesperson said the agency told Mosaic they would be required to obtain a state permit and conduct “extensive” groundwater monitoring.

In a statement, a Mosaic spokesperson said the company isn’t looking ahead to the potential profits of selling its byproduct, and is focused only on the study.

“The sole focus remains on the trial and adding to the body of science supporting safe uses of phosphogypsum,” spokesperson Jackie Barron wrote in an email. She pointed to the other 21 countries across the world that are reusing their phosphogypsum. “Any subsequent use of (phosphogypsum) will be informed by the study.”

Mosaic estimates 46 million tons of new byproduct need storage each year, according to the company’s petition, and they point to the environmental problems with gypstacks as a reason to explore new storage options.

The company plans to test three, 200-foot sections of the road and monitor radiation exposure during construction by using radon detectors placed around the location of the pilot road. There will also be several monitoring stations away from the site. Once the study is over, the company plans to destroy the road and return the phosphogypsum to its stack, Barron said.

The EPA’s review of Mosaic’s request, first filed in March 2022, is not yet complete, according to agency spokesperson Shayla Powell. There’s still no set date for a formal decision, but the agency expects one in the coming months.

“EPA will only approve the project proposed by Mosaic at its New Wales facility if the Agency determines that the proposed project is at least as protective of human health as placement of the phosphogypsum in a stack,” Powell told the Times in an email.

How risky is the plan?

Phosphogypsum contains radium-226, which emits radiation during its decay to form radon, a potentially cancer-causing, radioactive gas, according to the EPA.

Mosaic claims the maximum average radium-226 concentration used in its road will be 35 picocuries per gram, measured before it’s removed from the gypstack. A picocurie is a measurement of the rate of radioactive decay of radon. That level, Mosaic claims, is “well below” the federal risk threshold of 3 in 10,000 people developing a fatal cancer.

Truck drivers hauling the material “would be exposed for a period of a few weeks to a month,” according to Mosaic’s application, though the company says the amount of gamma radiation would be “negligible.” Mosaic says the same about the workers who would build the road itself.

The phosphogypsum will be mixed into a 10-inch thick road base, records show. On top of it, a 4-inch layer of asphalt will pave over the base.

The closest residence is more than 3 miles from the test road, and as part of its petition Mosaic determined there would be no adverse impacts on minority or low-income communities in neighboring areas.

The company isn’t doing a new risk assessment for the pilot project, though, because it’s relying on an earlier analysis done in 2019. That assessment, part of a request by the Fertilizer Institute, was first approved — then in 2021 subsequently rolled back — when the EPA said there was important information missing from the application.

Mosaic says there’s no need for a new risk assessment because the “risk considerations and inputs are virtually the same,” Barron said, and the new project’s scale is smaller than what was first proposed in 2019. But a new risk assessment is an important step for determining just how safe the project will be, Whitlock said.

“In order for you to say you’re attempting to flesh out the science of a project and do a pilot study, you cannot do so and make any meaningful advancements if you don’t have a risk assessment of what you’re trying to do,” Whitlock said. “I mean, it’s a ludicrous proposition.”

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative founded by the Miami Herald, the South Florida Sun Sentinel, The Palm Beach Post, the Orlando Sentinel, WLRN Public Media and the Tampa Bay Times.