Vulnerable, young corals in Florida's reef are being protected with biodegradable, 3D-printed cages in an effort to prevent lab-grown coral from being eaten by natural predators at sea.

Keri O'Neil, the director and senior scientist of the Coral Conservation Program at The Florida Aquarium, said Florida's Coral Reef is threatened by both pollution and rising temperatures.

"All of these things stress corals and throw off their natural balance, which leads to increased incidence of diseases like stony coral tissue loss disease," she said.

RELATED: Viruses that supercharge red tide are identified by USF researchers

Coral reefs are a critically important ecosystem to Florida because they support tourism by protecting our beaches.

“They really are a natural wonder of our oceans. The corals themselves are what builds the coral reef framework. They are like the trees that support all the organisms in the rain forest," O'Neil said.

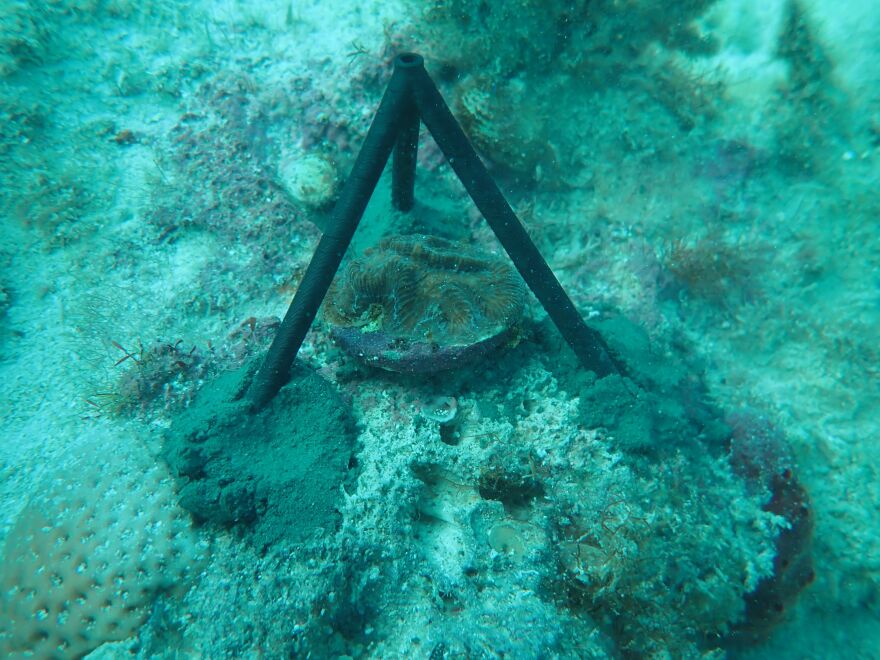

So, researchers at the aquarium partnered with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute in St Petersburg to not only plant lab-raised coral in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary back in January, but also to protect them with what they’re calling “coral defenders.”

"It's literally just like a little teepee that goes over the coral, but it keeps the larger parrot fish from being able to get their jaws around the young corals," O'Neil said.

“What we wanted to do was develop something that could easily be deployed by divers, but was also fairly quickly biodegradable, so that divers don't have to go back and remove the structure after it's put in place.”

The coral defenders are made of biodegradable plastic called PHA. Similar to a potato starch, it naturally breaks down when exposed, especially to salt water.

The little tripods are expected to last about a month before degrading.

This invention was inspired when pesky parrot fish recently gobbled up some newly planted brain coral on Florida's Coral Reef off the coast of Miami-Dade County.

The coral had been grown in a lab for over a year to restore receding wild populations.

Brain coral is a fairly common species, found in relatively shadow shallow water and even into some of our deeper reef areas, but almost half of them were lost with stony coral tissue loss disease.

“It is in need of restoration and it is a large framework building coral species,” O’Neil said.

“What we still don't understand is exactly why the predation is higher in some areas than others.”

She said the aquarium is working with fish behavior biologists to understand why certain areas are so much more susceptible to predation.

Stephanie Schopmeyer is a research scientist at the FWRI’s coral program.

“Brain and cactus corals were the species that we out planted this time. And these species have not been, I wouldn't say, heavily used in restoration activities in Florida up until now, so we're still kind of learning the process of how and when and where to out plant these corals,” she said.

Their goal is to capture that first two weeks when predation is typically higher and then monitor a total of 18 months.

“Are they experiencing additional predation? Are we're seeing actual tissue loss over time? Do these corals also experience other types of predations on the reef — which is common, either from fire, worms or snails? And we pretty much track them and track their condition over time,” Schopmeyer said.

The scientists hope this simple technique will prove to be another tool in Florida coral conservation toolbox.

“The main goal is to really figure out the best way to out plant these corals and get them to survive on the reef … there's a lot of trial and error, and there's a lot of kind of building upon what you learned last time,” Schopmeyer said.

“I really think this project demonstrates that because each time we do an out-planting now … we're learning a little bit more. We're hopefully advancing the art and the science of coral restoration to really promote the recovery of Florida's Coral Reef.”