As voters went into the polls Tuesday, many remembered a more grim Election Day from a century ago.

It was 1920 and, in Central Florida, Ocoee had a large Black community that was organizing to vote like never before. They put together voter registration drives, marches and secret voter education workshops in churches.

But their grassroots efforts were not welcomed by a lot of the leadership of that time.

“The KKK certainly was an intimidating factor in suppressing the Black vote. But that was not the main instrument of oppression of the Black vote. It was the threat of losing their jobs. It was an economic threat,” said FIU professor emeritus and historian Marvin Dunn.

Adding to that, white leaders also deterred Black voters with poll taxes and voter “qualification tests” that asked questions like: “How many bubbles are there in a bar of soap?”

One of the many Black citizens who were turned away at the polls was Mose Norman, a successful farmer and businessman. He insisted a second time and was turned away again.

After the polls closed, a white mob went looking for him. They ended up at the home of Julius “July” Perry, another successful member of the Ocoee Black community and one of its most politically active leaders.

There were reports of two white men being killed at a shootout at the house. The white mob drove Perry to Orlando and lynched him. They killed dozens of Black citizens that night, burning their homes and two churches.

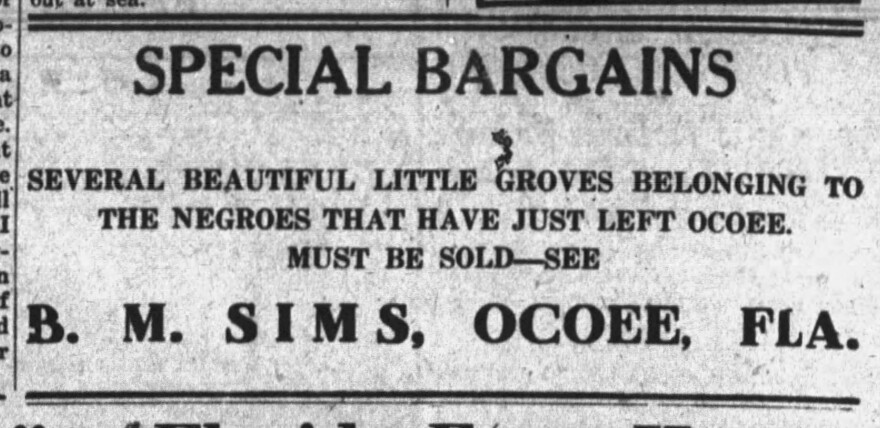

Those who survived, almost the entire Black population, fled the town and never came back.

WLRN’s Luis Hernandez spoke with Dunn, who is featured in a new podcast series by Ozy Media that explores the story of the Ocoee Massacre. You can find it by searching the history podcast “ Flashback” on any podcast app.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

WLRN: You’re from central Florida, when did you learn about the Ocoee Massacre?

DUNN: I didn't learn about the massacre until I was a grown person doing this research. I had never heard of what happened in Ocoee, although I grew up about 40 miles away. My dad was an orange picker and he would go to Ocoee to pick oranges.

I do remember my dad would talk about how mean Ocoee was. He said he would go over there, usually, a white man was driving the truck to take him to work. When they would leave at the end of the day, if the white man stopped his truck to start talking to one of his buddies, my dad said that they would get off the truck and walk because they needed to get out of Ocoee before the sun went down. And that was in the 1940s and early '50s.

Florida has a dark and long history of lynchings. Actually, if you lived in Florida during the lynching era as a Black person, you are more likely to be lynched than if you lived in Mississippi. So these stories are almost always buried. They're never brought to the fore unless some researcher takes the risk of making them known.

It was the presidential election of 1920. What was the social and political climate back then?

Intense. Women finally had gotten the right to vote and were going to vote for the first time. Now, Black women were more active in seeking the vote than were Black men.

And what led up to this event was that a Republican judge, John Cheney, was running for the United States Senate. And in order for him to win, he would need Black votes. All Black people registered for the Republican Party because they weren't allowed to register as Democrats. My parents were Republicans in the 1940s, as a matter of fact.

The main thing that they did to deter Black people from voting was to claim that they had not paid the poll taxes. And that was what happened when July, the main character in the story, went to vote with Mose, another very active Black Republican.

They were told you can't vote because your poll taxes aren’t paid. Now, these were two of the most active Black Republicans in the county trying to get other Blacks to vote. So why would their poll taxes not be paid? And thus began the confrontation at the polls that led to ultimately the attack on July Perry's home.

It wasn't until this year that a bill passed mandating the teaching of the Ocoee Massacre in Florida schools. How should it be taught?

It is very important that it’s in the curriculum, but it bothers me that they singled out Ocoee. That was not, as far as we know, the largest killing of Black people by whites in Florida — that happened in Newberry in 1916. In my view, it should not be just the Ocoee Massacre that is taught in Florida schools. The history of lynching and anti-Black violence should be taught in schools.

[It should be taught] carefully, very, very carefully and only with parental permission and only to secondary students with someone who knows how to lead a discussion about such sensitive things and knows how to respect the feelings of those who may be uncomfortable. And help kids appreciate not just the facts of what happened, but the feelings, the emotions that will surface that were experienced by people who had to experience these kinds of things.

Black history is important, but teaching people the facts of what Black person invented this and what Black person invented that is not nearly as important as teaching the experience of being Black in America during this dangerous and terrible time.

For you, what significance does the Ocoee Massacre hold today?

The same thing is happening today as we speak. The Black vote is being suppressed. And I will tell you this, the same response to that black vote suppression is happening now that happened in 1920 in Ocoee when Black people did go out to vote.

And in Miami, when the Klan did what they did to intimidate Black voters in 1939. That year marked more Black votes than have ever voted before in Miami. And today we see the Black vote being suppressed around the country. What do you see happening? People lining up at the polls and system that they would not be denied their vote.

So every attempt that I know of at suppressing the Black vote in history has backfired, including in Ocoee.

WLRN Sundial intern and production assistant Suria Rimer contributed to this story.

Copyright 2020 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM.