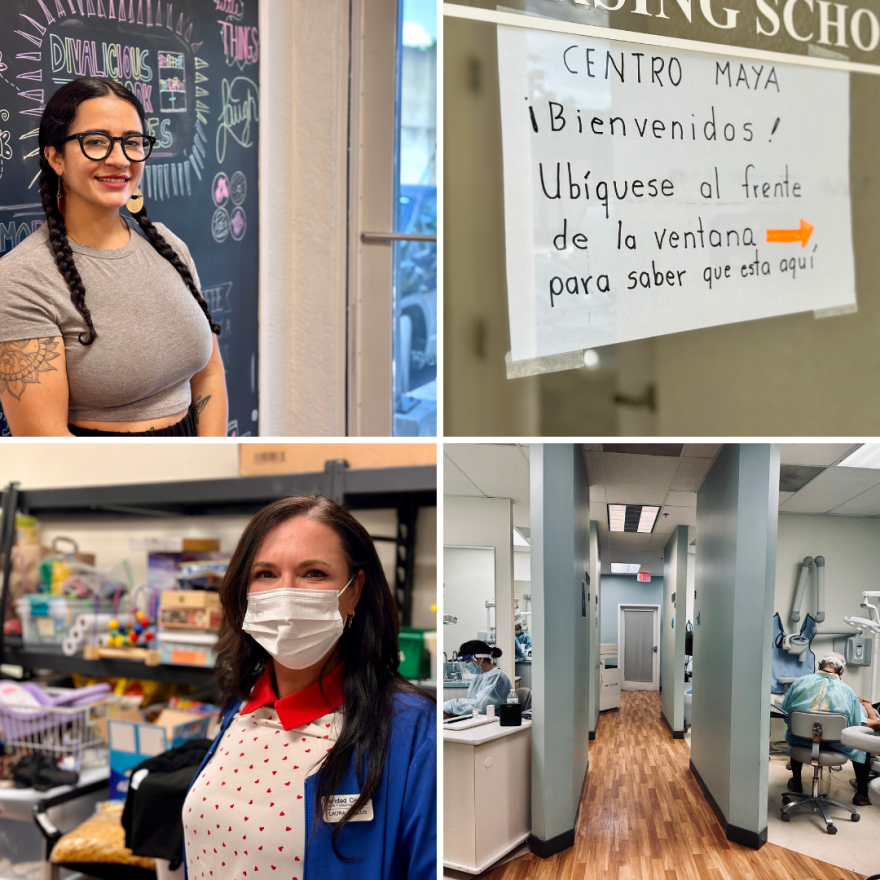

Across the street from Lake Worth High School, dozens of immigrants sat in a dark room, bowing their heads in prayer. This isn't a church though — the group is gathered at the Guatemalan-Maya Center to learn more about SB1718, Florida's aggressive new law targeting undocumented immigrants.

Historically, many Guatemalan immigrants have come to the area. To handle the growing influx of the population, the center had recently moved to a bigger location — and so many people showed up for this town hall that they needed to use an overflow room.

After a group prayer, about 60 people — mostly Guatemalans, including indigenous Mayans — listened to a Zoom call with legal experts from Florida’s American Civil Liberties Union, who were trying to clear up misinformation about the law.

The new law sent shockwaves across various immigrant communities in South Florida.

But a volunteer at the center, who asked WLRN not to use her name due to safety concerns, said it is especially frightening for her fellow Guatemalans who only speak Mayan languages.

"They don’t speak Spanish. They don’t speak English. They don’t understand exactly what’s happening because they have other languages,” she said. "We have like…Mam, Popti, Q’anjob’al, Kiiche [Mayan languages]... it’s like, 20 dialects."

The volunteer speaks most of those languages. Her kids were born in the U.S., so her family is what people refer to as mixed-status. Despite her own fear and uncertainty, she volunteers her time to translate information about the law for her indigenous neighbors. Her guidance, at times, has been enough for some to not flee the state.

“I know a little bit how [the law] works so that’s why some people stay," she said. "And they say, 'Please let us know what happens in the future. Please call us. Explain [to] us.'”

The new state law targeting undocumented people takes effect July 1st. Like many Guatemalans, she moved to Lake Worth Beach after fleeing poverty and ongoing violence from gangs and the government in her country.

As the date comes closer, many people are facing being displaced again as they wrestle with the decision to trek north toward immigrant-friendly states.

She said she helped a few people leave already — those who felt it too risky to stay in Florida. “Personally, I’m so scared. Everything [has] changed because the community is so scared. A lot of people are moving,” she said.

“I contacted Massachusetts and three families moved there. Pennsylvania — two families moved to Pennsylvania. But sometimes they don’t have family and they don’t know how they can go there. So, it’s so, so sad.”

Provisions of the new law

Among many provisions, the new law signed by Governor Ron DeSantis strengthens requirements for employers to e-verify workers’ immigration status and invalidates out-of-state identification cards such as driver’s licenses.

“People are gonna come if they get benefits and so what you wanna do is say there’s not benefits for coming here illegally,” said Governor DeSantis, at a press conference shortly after signing the bill.

In the official statement signed on May 10th, DeSantis said "the Biden Border Crisis has wreaked havoc across the United States and has put Americans in danger” and that "the most ambitious anti-illegal immigration laws in the country" ensures that "the Florida taxpayers are not footing the bill for illegal immigration."

The Guatemalan volunteer says people in her community and advocates in Lake Worth Beach have been pushing back against those claims, especially about danger.

“They’re [immigrants] not criminals," she said. "They’re not the cartel. They’re not the terrorists. They are people [who] come for a good future. So it’s sad he wants to put his rules in this state. It’s not fair.”

Lake Worth Beach has been a safe haven but for those who stay, the fears are compounding because many immigrants are unsure if they’re allowed to use medical services.

One provision requires hospitals that accept Medicaid to ask each patient about their immigration status and report the data to the state. She had recently assured another immigrant mother who was afraid to take her sick child to the hospital.

Danna Torres, Clinic Director at the Guatemalan-Maya Center, said she is especially worried about the chilling effects of the law, especially in regards to pregnant women and children.

“What we have to counter is — 'Yes, you still can go to a hospital. Yes, You can still get emergency care. Yes, You're still going to have access to medicine,'” Torres said.

At the center, outreach workers help more than 1,000 immigrants a month with early childhood education, medical care and other assistance.

Numbers rise — so does misinformation

Torres says the numbers keep rising. And so is misinformation about what people can and can’t do.

“It's just that one question that's now going to be asked and you can decline to answer it. So I feel like if we can just focus on that piece of it and not add on to it, we can help minimize the fears.”

Laura Kallus, who runs the non-profit Caridad Center in Boynton Beach, says she’s facing the same challenges. Kallus says the lack of primary and prenatal care access could exacerbate racial disparities in the healthcare system.

“Many pregnant women can get Medicaid for the during their pregnancies. And we're going to be seeing less of that, obviously, because women are scared,” Kallus said.

“And so what you really worry about is women who are not going to get the primary care or the prenatal care that they need,” she said. “And we know what that does to communities, especially communities of color.”

Caridad is a healthcare clinic serving uninsured children and adults who live below the poverty level — retired, volunteer doctors help patients through various procedures.

“If patients delay seeking care, and many of our patients have chronic conditions so they need medications and they need ongoing care... so if they delay or decline to seek care it can be really catastrophic for their families," she said.

GOP Rep. Rick Roth, a farmer who represents parts of Palm Beach County, says he supports the law — yet he is simultaneously trying to play down its potency.

He is drawing attention to its loopholes as he urges immigrants not to leave Florida — because the agricultural industry is losing employees.

In an interview with NPR, Roth said because the law doesn't include more funding for enforcement, it was designed to be "more of a political bill than policy" — a law "meant to scare migrants."

Torres at the Guatemalan-Maya Center says even critics of the law are focusing on how this it will affect the economy, rather than how it will affect people.

“You see people sharing videos about 'Look at these construction sites. They're now empty.' And yes, like that is an important point to make. But also, all those jobs are very exploitative,” Torres said.

She says the Guatemalan-Maya Center launched a fundraiser to support people who decide to leave the state — while at the same time trying to convince them to stay.

“And so we want to preserve our communities because we love our communities, because they contribute so much to us and because they're a part of us, not because of their labor value," Torres added.

Copyright 2023 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM.