“Excuse the volume, chaos and mess, but we are learning here,” reads the sign hanging in a classroom for 3-year-olds at The Creative Learning Center in Kendall.

That learning will continue next month — but without thousands of dollars of federal aid.

It is one of the thousands of child care centers nationwide preparing for the financial challenge beginning in October, when billions of dollars of federal grant money expires.

The center's director, Emilu Alvarez, hopes it isn’t chaos, but she knows it will be difficult. And it likely will mean higher costs for parents

”We will have to raise tuition, and we may not be able to do the salary increases like we did before,” she said

Her school has about 250 students, most range from ages 2 to 6, including a kindergarten class. It costs about $170 a week for the preschool, depending upon the age of the child. The two-plus years of federal grant money helped hold down tuition hikes.

More than $24 billion in stabilization grants has gone to tens of thousands of licensed child care providers nationwide as part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021.

That program and others go away this Saturday, the end of fiscal year 2023 and the expiration date for funding allocated to accelerate the country's health and economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

A group of senators has pushed to extend the assistance through the Child Care Stabilization Act, which would provide $16 billion annually for the next five years. But a agreement seems unlikely given the looming federal government shutdown that could take effect Sunday.

“I had a mom [who] read the news about the Sept. 30 cutoff. She came to me and she asked me, ‘Is this going to affect me? What do you think? What's going to happen? How am I'm going to pay you?’” Alvarez said.

The school has been giving the parent a break on tuition for her twin 2-year-olds and after-school care for a first-grader – something extended to a few parents at The Creative Learning Center.

“But it's going to stop. All of that will stop now. All of that. That will completely stop.” Alvarez said.

Alvarez had a sheet of acronyms she used to keep up with the government grant programs that provided funding to child care providers during the COVID pandemic. On the sheet that hung in the employee lounge, she would pencil in how much money each grant was worth. The stabilization grants totaled $210,000 for her school.

Alvarez used the money to increase salaries, pay small bonuses — like $25 on a Publix gift card — and fix up the school by filling parking lot potholes, rehabbing bathrooms and putting up rain gutters.

She thinks it will be January when her school will start to see the pinch of the federal stabilization grants running out.

A stressor for families, billions lost for the economy

Child care is “a really, really difficult industry,” said Kyle Baltuch, senior vice president of economic opportunity and early learning for the Florida Chamber Foundation. “While it can be extraordinarily costly, the margins are still razor thin.”

A foundation study concluded the lack of affordable and high-quality child care costs the Florida economy more than $5 billion a year. Most of that cost comes from the lost availability for parents who miss work to take care of a child or choose not to work because paying for child care is not an option for them.

“It is a stressor for families and not just in the sense that it may inhibit a child's ability to learn long term, which it absolutely does. But right now, it is a stressor on our economy,” Baltuch said.

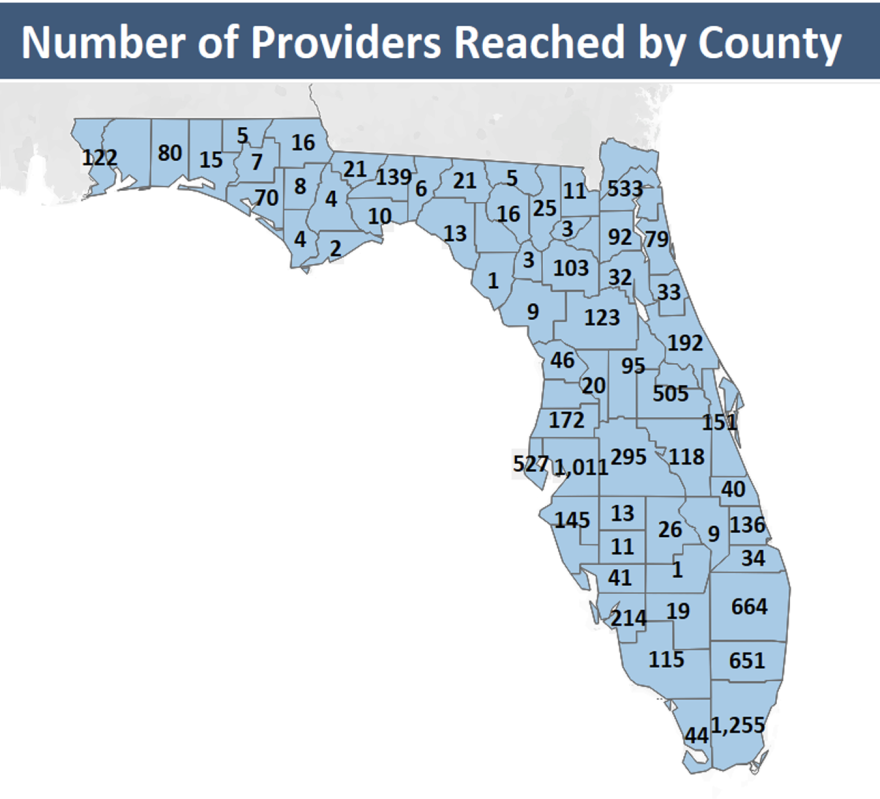

More than 8,600 child care programs in Florida received a total of $1.5 billion in stabilization grants. One out of three were in South Florida, including centers and child care homes.

“I think when you look at the costs of child care, the parents have to choose. ‘Grandma, help me out? Or auntie? Or do I just not work at all?’” said Antoinette Patterson, owner of One World Learning Center in Miami.

About 40 children attend the school on Northwest 27th Street. Tuition runs $185 per month for 4-year-olds. It is more expensive for younger children. That can add up to about $8,000 a year in a ZIP code where the median income is a little over $50,000 a year.

A child care center could have received tens of thousands of dollars in grant money over the past two years based upon enrollment, age of the children and location. A center could get additional dollars if it promised to spend at least 25% on raises or bonuses for staff.

Patterson used her grant money for operating costs like rent, utilities and supplies, in addition to staff pay.

“It was mostly to help a lot of our teachers because a lot of them are not making as much as I think they should make, but only because our revenue is not as high to give them what they deserve,” she said.

Starting pay at Patterson’s day care is $16 an hour. She offers vacation, sick days and personal days but can’t afford to pay for health insurance or offer a retirement savings plan. She has plenty of demand for child care, but has trouble competing for workers.

“I do get a lot of calls for parents wanting to enroll their daughter or son here. The problem is I can't get teachers. So I've had to turn children away because I don't have teachers,” said Patterson.

It’s the same challenge in Kendall for Alvarez at the Creative Learning Center.

“This year I have three empty classrooms because I can't find quality staff. And now with less money and less workforce retention, it's going to be harder to find,” she said.

Copyright 2023 WLRN 91.3 FM. To see more, visit WLRN 91.3 FM.