Hillsborough, Pasco and Pinellas County have been working together to plan for how to keep the roads open following an extreme weather event.

Rodney Chatman, Planning Division Manager with Forward Pinellas, said it makes sense, because the counties, which often work together on transportation issues, realize that “people’s travel patterns don’t stop at the county line.”

Hillsborough County’s Metropolitan Planning Organization worked with its counterpart in Pasco County, and Forward Pinellas, which functions as both the MPO and the planning council for the county. Together, they applied for a Federal Highway Administration grant to conduct a mobility study.

Chatman said they were one of only 11 pilot projects to be chosen for this particular study.

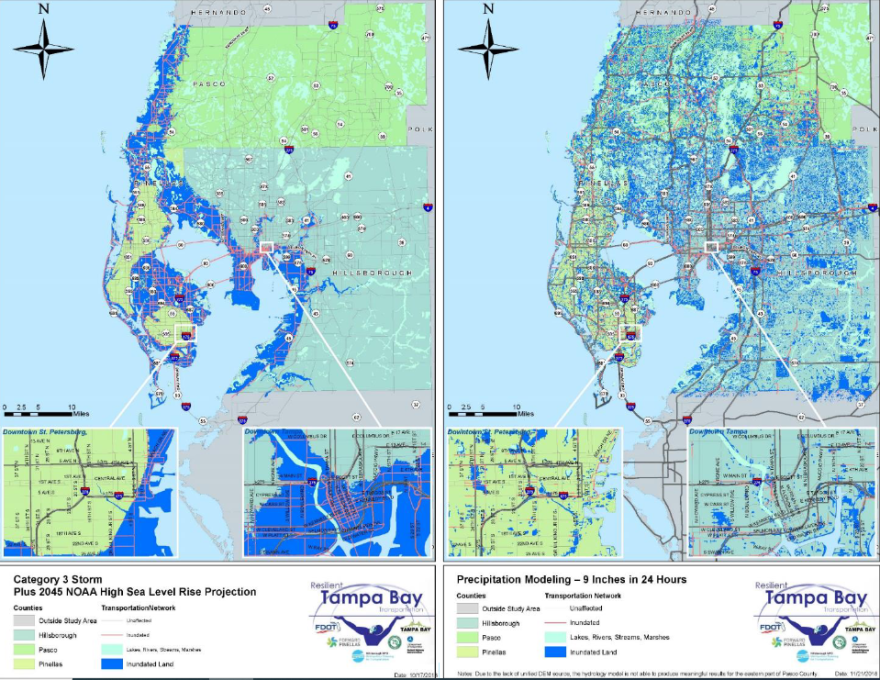

One scenario that was put together for the study was the impact of a Category 3 hurricane, along with nine inches of rain in a single day, factored in with predicted sea level rise by 2045.

The study predicted $175 billion in potential property losses from a direct hit by a Category 4 storm.

And to “evaluate the length of time an outage impacts the economy,” The Resilient Tampa Bay: Transportation Pilot Program Project conducted modeling from two days to a month.

For example, the study said it would be beneficial to make adaptations to Gandy or Gulf Boulevards if they became impassable for as little as two days. However, the study said it would be beneficial to the region to “enhance U.S. 19 and Roosevelt Boulevard, should they be out for a month.”

Chatman said his county, Pinellas, is among the most vulnerable, and often called, “a peninsula on a peninsula.”

And so, he said, “we have to live with water in a slightly different way than Hillsborough and Pasco does. And the results of the study determined that a lot of our coastal roadways, whether that be Gulf Boulevard, Bayshore Boulevard, other parts of Alternate 19, as well as roadways on the east side of the county, Fourth Street in St. Petersburg, even parts of Roosevelt and Ulmerton, were inundated with various degrees of water depending on the type of climate hazard that was modeled.”

Hillsborough’s MPO Executive Director Beth Alden said she traveled to New York to visit family following Hurricane Sandy and went to New Orleans five years after Hurricane Katrina struck there. She said storm damage became a roadblock to rebuilding in both places.

“Because all of a sudden you have a huge need for construction supplies. You have, of course, needs for fuel, you have need for medical supplies. And that's at exactly the same time that some of your key transportation infrastructure might all of a sudden become impassable,” she said.

But building or doing mitigation on roads and bridges gets expensive. And in Hillsborough County, officials are waiting to hear what the Florida Supreme Court says about the constitutionality of the one-cent transportation tax that was passed in 2018.

That’s money county planners were depending on, because Alden said the gas tax alone won’t cover all of the massive county’s maintenance needs - a county, which she said, “is larger than a couple of states and more populous than 10.”

So the report prioritized roads by how critical they are.

“Meaning from the point of view of emergency evacuation and how many people typically use that road in any given day. We also prioritize them based on our most vulnerable populations and their needs so we could focus on roads with the highest criticality score,” Alden said. “We could also focus on the investments that are the least cost. So you can kind of think of that as like, you know, that your biggest return on investment, you know, let's at least do some of the basic things.”

According to The Resilient Tampa Bay: Transporation Pilot Program Project, about "39% of the region's populations lives in areas at risk from flooding, and nearly two-in-five of the region's 1.1 million jobs are in zones susceptible to hurricane storm surge."