When Hurricane Idalia collided with the rural Big Bend region of Florida at 7:45 a.m. on Aug. 30, it heaved nearly 10 feet of storm surge into the two nearest coastal towns, Steinhatchee and Cedar Key.

Ninety miles south of landfall, in Crystal River, the surge was so bad that authorities had to take an airboat to tour the town’s streets.

And even 150 miles away, the storm pushed more than 4 feet of surge into Tampa Bay. One man paddled a pool floaty over what was once a promenade. Navin Singh, of Tampa Bay Storm Chasers, watched water crest a 6-foot seawall, flooding volleyball courts and streets. It was the largest surge Tampa had seen since the 1921, when, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Tampa Bay/Tarpon Springs Hurricane brought 11 feet of storm surge to the city.

Idalia’s surge was able to reach Naples, some 250 miles south as the crow flies from landfall, flooding streets and construction sites.

Here’s a look at the factors that allow a relatively compact storm such as Idalia to send surge down nearly the entire west coast of Florida, and the strokes of luck that kept the damage from being worse.

Surge and the dirty side

Hurricanes in the northern hemisphere all rotate counterclockwise, explained Brian Haus, director of the SUSTAIN Laboratory at the University of Miami. Haus and his team use a massive water tank to simulate and study storm and ocean interactions.

As a storm moves forward, its right-hand side is more destructive, and is known colloquially as the “dirty” side. Surge, therefore, is far worse on the right-hand side of a storm. Idalia’s landfall in the Big Bend region put everything south of that point on the dirty side.

The closest town to landfall on the dirty side of Idalia was Steinhatchee, 15 miles south, which saw just over 9 feet of surge, according to the Suwannee River Water Management District.

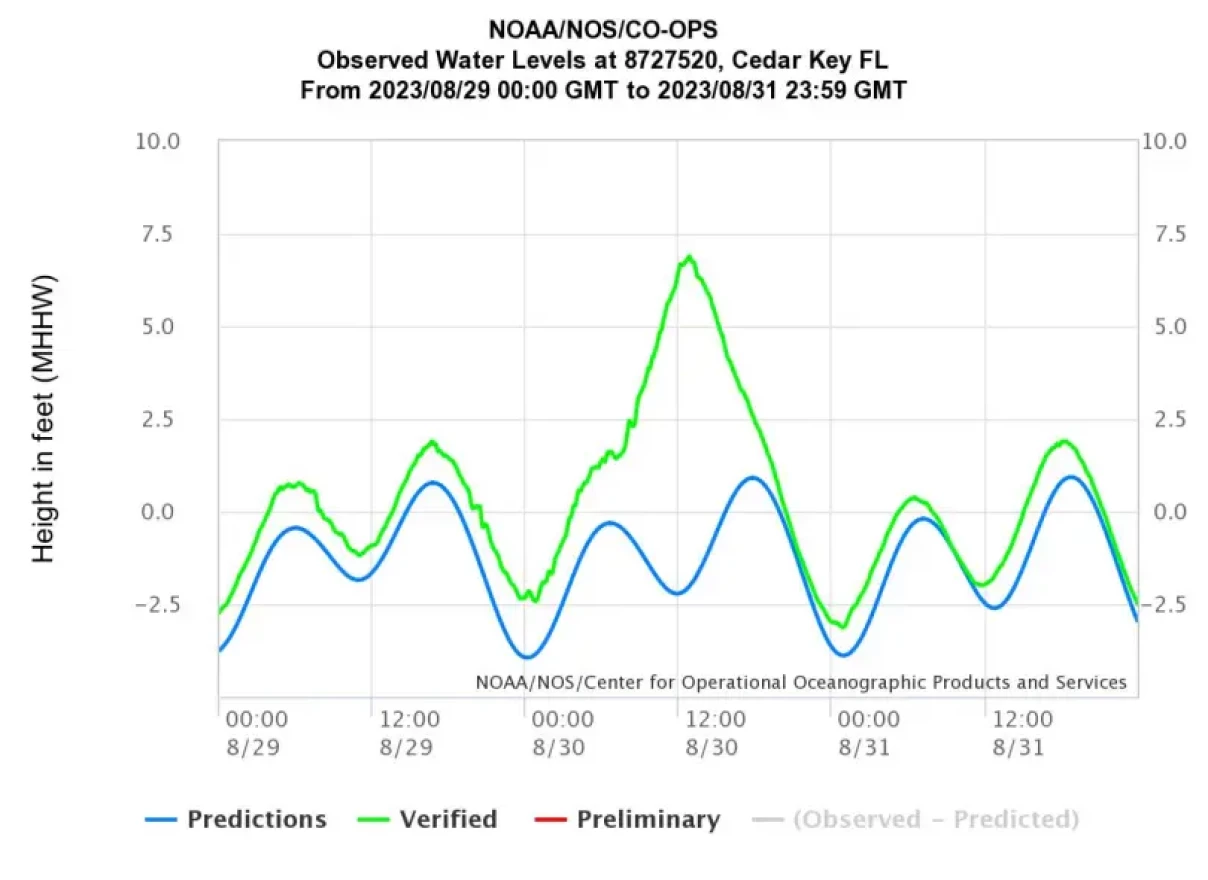

Fifty miles away, the NOAA tide gauge at Cedar Key shows a surge around 7 feet above sea level (9 feet above the expected tide). The town was under evacuation orders, but Andy Bair, owner of 164-year-old Island Hotel, decided to stay.

“We knew we were going to take a pretty good lick,” he said. Even so, he locked up the hotel, and he and his wife rode the storm out in an elevated condo down the block.

The hotel stands on a small knoll, slightly elevated from the rest of town, which might be why it’s still upright and in good shape after more than a century of storms.

“As day broke, I watched the water come up in the bay behind the condo, and I said, ‘Oh God, when that tide starts to rise and the surge gets going, we’re going to get really slammed,’” he said, anticipating a long surge.

But the surge left quickly, before the incoming tide could stop it. It turns out, by sheer luck, the surge was timed almost perfectly with low tide. Had that surge hit at high tide, surge would have likely been 10 feet.

“I thought I was going to have to deal with this thing till 2 in the afternoon. So wow, what a break I got. … I’m real happy about that,” he said.

As the surge quickly ebbed, he went to check on the old hotel and was pleasantly surprised.

“It had flooded about 5 feet into the basement. The basement has an earthen floor, so the water just sunk back into the ground,” he said. A small part of the hotel flooded, but the cleanup was not severe.

The rest of the town didn’t fare so well. “There were a couple of coffee shops down the road that were about 5 feet in water. A couple of the buildings near there just disintegrated,” and some of the businesses on Dock street “got hammered really bad,” he said.

Bud Adams, Bair’s son-in-law, who runs the hotel these days, said that when he walked through town after the storm passed, “most of the water had receded, but there was damage everywhere.” There was a big crab boat on a trailer that had floated behind the hotel and was now stranded, sitting akimbo. “The debris was incredible,” he said. “We were very fortunate. A lot of our friends and neighbors were not. We tried to do the best we could to open and provide some food and drink.”

Incredible #Idalia storm surge 6’ and counting here at Cedar Key, FL pic.twitter.com/8MzaHJpWce

— Jim Cantore (@JimCantore) August 30, 2023

He and Bair were able to find some ice and open the bar six days after the storm hit, and opened the restaurant two days after that. They actually had two guests in the hotel that night as well.

Factors of good fortune

Bair’s and the quaint hotel’s good fortune was dictated by a few key factors.

Low tide: By pure happenstance, Idalia’s surge near landfall, and even hundreds of miles down the coast, coincide with low tide. “The fact that the tide was low was a great benefit for Cedar Key,” said Haus, of the University of Miami. “Otherwise it would have been worse.”

Areas farther south, such as Crystal River, Tampa Bay and St. Petersburg, all had significant, if not surprisingly high storm surge, given their distance from landfall, but still benefited from the surge synching up with low tide.

Speed as a blessing and a curse: Idalia was somewhat fast-moving as it crossed the Gulf of Mexico at 16-18 mph, and fairly narrow, with hurricane-force winds extending only 25 miles from the eye, and tropical-storm-force winds extending 175 miles. Both factors made for a brief surge.

By comparison, Hurricane Lee was slower, and four times as wide. Lee puttered to 6 mph before it made its turn north away from Florida last week, and the latest update showed hurricane-force winds extending a whopping 100 miles from the eye, and tropical-storm-force winds extending 300 miles, making the storm 600 miles wide.

“Storm surge is created primarily by the wind field pushing water onshore,” Haus said. “So if a storm is moving slowly, it has an opportunity to push more water into the coastline, and push it farther up into bays and estuaries — it increases the time over which that storm surge is active, and allows more water to build up.” Accordingly, storm surge at the upper end of Tampa Bay was actually deeper than it was at the mouth.

Back in Cedar Key, Bair’s joy at seeing the surge exit his back-bay area quickly, before high tide showed up, was a function of Idalia being fast and small.

Haus said the diameter of the storm matters, too.

Wider storms build longer surges because they’re acting on water longer. Another detail key to Tampa and Naples’ surge: The farther away from the eye you are, the weaker the wind, but the longer that wind has to push on the water.

“You can get hundreds of miles from the eye of the storm and still have really strong, large wind fields, and they can be distributed over a wider area, so that can make a long time for onshore winds. There’s a large distance over which onshore winds to the right of a storm are pushing on shore.”

The shallow slope of the Gulf Coast also makes surge worse. Haus said that “because it’s shallow and the wind is really strong, it’s pushing that whole shelf, all the way to the bottom, it’s pushing that water in.”

🚨#WATCH: As people, paddleboard, bike and float on a large inflatable duck during Hurricane Idalia

— R A W S A L E R T S (@rawsalerts) August 30, 2023

📌#Tampa | #Florida

Many people have taken shelter in Tampa, Florida, as the powerful Category 3 Hurricane Idalia makes landfall on the northwest coast of Florida. This storm… pic.twitter.com/bcLcy41oMw

The Atlantic coast has a steeper shelf with deeper water close to shore. That deep water just isn’t as easy to push.

Shore type: As with a sponge and a plate, a soft shoreline with nooks and crannies absorbs more water and wave energy than a shoreline of hard surfaces. Haus said that in general, mangroves, marshes and barrier islands without any construction on them impede the flow of water, dissipate wave energies and reduce the overall impact of a storm. By contrast, he said human-made objects such as seawalls, roadbeds and buildings reflect and redirect waves, but they don’t reduce their power.

Steinhatchee, the first town south of the eye, was protected by a marsh area, but still had 9 feet of surge.

Big Bend is one of the least developed coastal areas of the state, and its shoreline, when viewed from above, looks like a tattered sponge. Taylor County, home to much of Big Bend, has a population of 21,815 spread out over 1,232 square miles.

By comparison, Broward County has 90 times that many people packed into an area about one-third the size (two-thirds of Broward is occupied by water conservation areas west of the Sawgrass Expressway).

Sea-level rise: It turns out that the Big Bend region of Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico in general are experiencing sea-level rise at a faster rate than most other parts of the world.

The difference is due to a few factors. Hot water takes up more space, and the Gulf is typically very hot — even hotter this year. That greater volume adds depth. Secondly, a natural phenomenon known as Rossby Waves, massive 600-mile-wide undulations in the ocean that are so large and slow that they’re invisible to the human eye. They can take decades to cross an ocean, and move in a westerly direction, meaning they pile water up on the eastern seaboard of the U.S. and into the Gulf.

Climate change also causes tropical storms to be more intense due to higher water and air temperatures.

All told, mean sea-level rise has been about 1.5 millimeters per year since 1900, and more than 3 millimeters per year since 1992. In parts of the eastern Gulf, it’s been a rapid 10 mm per year since 2010. The waters near Cedar Key have risen more than half a foot in the last century, according to NOAA — more water for any storm to push.

All these factors play a role in an Idalia storm surge that was brutal close to the eye, but could have been much worse with a wider, slower storm that hit at high tide, or collided with an area with a higher population.

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative founded by the Miami Herald, the South Florida Sun Sentinel, The Palm Beach Post, the Orlando Sentinel, WLRN Public Media and the Tampa Bay Times.